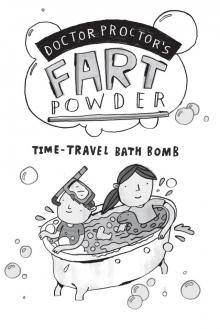

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb Read online

Page 12

“So what if I am?” Nilly said with a yawn. “So sue me.”

“Sue you? I’ll court-martial you!” Grouchy was so angry that his eyeballs were quivering.

“Fine,” Nilly said, sliding down out of his saddle. “After my morning bath.”

He hurried into the tent, but had just managed to get one foot up onto the edge of the bath when he felt something very sharp poke him in the back. He turned round and found himself face to face with Grouchy, who was holding a rapier. Nilly cursed because he saw that the tip of the deadly blade was pointing right between his eyes, just a few millimetres from his forehead.

“Tell me,” Grouchy said. “Are you really Napoléon? Take that thing off your nose so I can see.”

“Ten hut!” Nilly commanded. “Jump!”

But his brisk orders didn’t seem to have any effect on the marshal.

“Guards!” Grouchy hollered without taking his eyes off Nilly. “Guards, get in here now!”

“Did someone call?” Handlebar and Fu Manchu entered the tent and stood behind Grouchy.

“Arrest this imposter!” the marshal screamed. “Tie him up and roast him over a low heat until he admits that he’s an English spy. Then we’ll hang him from the nearest tree.”

“All right,” Handlebar sighed. “Man, nothing but work, work, work.”

“And what’s the point to roasting him first?” sighed Fu Manchu. “Why not just hang him right away? We haven’t had breakfast yet.”

“Snap to it!” Grouchy howled.

“Yes, sir, Marshal.” They sighed and started towards Nilly.

“Wait!” Nilly said. “The marshal is the one who should be bound.”

“Interesting,” Handlebar said, stopping in his tracks. “And what else?”

“Tickle the bottoms of his feet with bird feathers until he promises to be a little nicer. And then send him home to his mother with a note.”

“Tie him up immediately!” Grouchy growled. “Otherwise I’ll hang you too!”

“Oh, you will, will you?” Handlebar asked, swinging his rifle slightly so that it happened to be pointing right at the marshal.

Grouchy paled. “Listen up, my good men,” he said. “I will promote you to lieutenants if you do as I say. Think about that: officers of the French army. And in addition, I will agree to not hang you. What do you say?”

Handlebar and Fu Manchu looked at each other. Then at the marshal. And finally at Nilly.

“What do you say, Generator? Do you have a better offer?”

“Yeah,” Nilly said, scratching inside his ear with his left index finger. “Breakfast. Fresh-baked bread with strawberry jam.”

“Fresh-baked bread,” Handlebar repeated, looking at Fu Manchu.

“Strawberry jam?” Fu Manchu repeated, looking at Handlebar.

“Listen up, my good men . . .” Grouchy said. But that was also all he had time to say, because the next instant he had a holey right sock stuffed in his mouth and, after quite a bit of tying, he too had been transformed into a corn on the cob.

“Take him out and tickle him,” Nilly said, and started unbuttoning his uniform. “And it would be great if you guys could hang a DO NOT DISTURB sign on the door, because I’m going to take my morning bath now.”

THE ENGLISH AND the Duke of Wellington encountered no opposition that day at Waterloo. They just marched right into the Frenchmen’s deserted camp. There they found countless abandoned rifles and cannons as well as a dungeon containing a half-crazed woman with a wooden leg and a long, black trench coat, plus a tent with a sign on it that said do not disturb in French. The English, who are a very polite people, would not normally have ignored this kind of message, but since they couldn’t read French, they walked right into the tent. But all they found there was a bath where the last of the soap bubbles were just disappearing.

“This is embarrassing!” the Duke of Wellington told his officers, angrily kicking the bath. “And here I was, looking forward to being a hero with huge casualty figures on both sides. And then we win without firing so much as a single shot!”

One of Wellington’s officers whispered something into his ear.

“Jolly good!” Wellington exclaimed. “I’ve just had an idea! Listen, when we get home, we’ll tell the royal court that we fought valiantly and trounced these Frenchmen. We’ll say that it was the biggest battle ever! And that strange little Frenchman in the nightshirt who fell out of the sky and thinks he’s Napoléon, we’ll say he is Napoléon!” The duke laughed loudly. “And then we’ll ship him off to a remote island so he can’t expose our deception should he ever regain his senses!” The duke leaned over to his officers in a conspiratorial manner and whispered, “And no one tell anyone what actually happened here in Waterloo. Agreed?”

All of the officers answered in unison, “Agreed!”

NILLY WAS SITTING on a chair next to the bath in the Hôtel Frainche-Fraille. He was wearing a pair of trousers that were far too big and a shirt that he’d borrowed from Madame Trottoir at the reception desk. But at least these clothes were dry, unlike the sopping wet blue uniform he’d arrived in, which was now hanging over the back of the chair dripping. Nilly rested his head on his hands and stared sorrowfully down into the dark water. The others weren’t here! He was totally alone. Apart from a seven-legged Peruvian sucking spider named Perry who was sitting inside a toothbrush glass next to a tube of Doctor Proctor’s Fast Acting Superglue on the shelf under the mirror. Perry listened quietly and seemingly sympathetically, while Nilly went on and on in despair:

“What do I do now? I can’t take this anymore. You know what I want to do? Go back to when we moved to Cannon Avenue and make sure I never meet Lisa or Doctor Proctor! I can make different friends who would be way less trouble!”

Nilly reflected on this.

“All right, maybe I wouldn’t have made any other friends. But I would have rather been alone than . . . well, alone, like I am now. I’m sorry to say this, Perry, but you actually aren’t much company.”

Nilly kicked the side of the bath so it made a deep rumbling, submarine-like sound.

Then he hopped down off the chair, left the bathroom and crawled into his bed.

The last thought he had before he fell asleep was that at least tomorrow he would get to have breakfast.

Nilly was in the middle of a dream about a sunny-side-up egg the size of a manhole cover and slices of bacon so fresh that they were still oinking when he suddenly woke up.

He’d heard something.

Something from the bathroom.

Bubbles . . . as if something were coming up from the depths . . . the depths of water, space and time . . . as if something had arrived . . . in the time-travelling bath? Nilly sat up in bed and stared through the darkness at the bathroom door, listening with his heart pounding. But there weren’t any other noises.

He called out cautiously, “Lisa?”

His voice sounded so naked and lonely in the dark. Especially since there was no response from the bathroom.

“Doctor Proctor?”

Still no response.

“Juliette?”

Still nothing.

Nilly curled up under the covers. He had no desire to call out the fourth name, didn’t even want to think it. Because even his thoughts stuttered at the thought of R-R-Raspa.

He lay like that for a few minutes. Nothing happened. And for guys like Nilly there’s only one thing worse than when really scary things happen and that’s when nothing happens. So he jumped out of bed, crept still half-undressed over to the chair where the wet uniform was hanging, pulled the sabre from the belt, tiptoed over to the bathroom door and yanked it open while screaming:

“Banzai, Englisher Schweinhund!”

Nilly stormed in swinging his sabre and slicing the darkness into three, four, yes, maybe even five pieces. It wasn’t until he was sure that the darkness and everything in it had been thoroughly carved up that he flipped on the light switch. From the toothbrush glass on the sh

elf under the mirror, Perry stared at him in terror with his black compound eyes. But otherwise there was nothing there, at least nothing that hadn’t been there before he’d gone to bed.

Wrong.

An empty wine bottle with a cork was floating in the motionless water in the bath.

He looked at it more closely. Wrong again: it wasn’t empty at all.

Nilly fished the bottle out, sank his teeth into the cork and pulled until it went plop. Then he turned the bottle upside down and shook it. A slip of paper fell out onto the bathroom floor.

He unfolded and read it. His eyes skipped down to the bottom. The smile on his face kept growing.

It was from Lisa.

“Well, well, Perry, my old friend,” he said, folding up the letter and checking his parting in the mirror. “We’re in business again. Sorry to deprive you of my company, but new adventures call. Tell me, what do you know about the French Revolution and beheadings?”

Gustave Eiffel

A MAN WITH an enormous handlebar moustache, an even more enormous potbelly and a pipe bet ween his lips was staring at the girl who had so unexpectedly appeared in his office. Not to mention the bath in which she had arrived. He squeezed his eye around his monocle, emitted a surprised “pff!” from his lips, and a cloud of tobacco smoke rose into the air between the bookshelves.

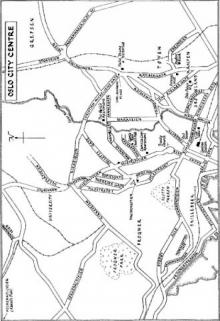

Lisa looked around. The walls were hung with drawings of buildings, bridges, breweries and other enormous things that start with B that you couldn’t fit in a normal piece of luggage. There were two drawings on the desk under the window, two empty bottles of red wine and a pouch of tobacco. The window faced a large, open and rather empty public square. Strikingly empty, actually. Apart from all the people with parasols and top hats strolling across it. There was something strangely familiar about this square, Lisa thought.

“Who are you?” the man asked. “And where did you come from?”

“I’m Lisa,” Lisa said, wringing out the sleeve of her sweater. “I come from Cannon Avenue in Norway. From sometime in the next millennium. You must be Gustave Eiffel?”

The man nodded and then had a coughing fit.

“I understand that you’re afraid, Mr Eiffel,” Lisa said as she climbed out of the bath.

The man waved this away dismissively, coughing, and then in a voice that was scarcely a hiss whispered, “Not at all.”

His face was now as red as a peony and he was clearly struggling to get air. When he finally did manage to breathe, his throat squeaked and his lungs gurgled. Then he stuck the pipe back into his mouth, inhaled, and said with a satisfied smile:

“Nothing serious, just a touch of asthma.”

It occurred to Lisa that Mr Eiffel didn’t seem quite as afraid as you would expect given that an unexpected bath and a girl who said she came from the future had just appeared in his office. And a second later, she knew why.

“The professor said there would be two of you,” Mr Eiffel said. “A certain Mr Nilly appears to be missing.”

“You talked to Doctor Proctor?” Lisa exclaimed. “Where is he?”

Mr Eiffel stuck a thoughtful finger in between two buttons on his shirt and scratched his stomach. “Unfortunately I am not exactly sure, moan amee. We had a very brief meeting, right here in this very room. And then he left. But, like you, he came in a bath. A time-travelling bath, as he explained to me.”

“And you believed him?” Lisa asked. “That he’d invented a way to travel through time?”

“Of course. I would have had a harder time believing the opposite, that no one would ever invent a way of travelling through time. I am an engineer after all, and I’m a hard and firm believer in people’s ability to create things. All you need is a dose of imagination and a little logic.” Eiffel smiled sadly. “Unfortunately, I myself only have the logic part of it, but not the imagination. If there’s one thing you can never have enough of, it’s imagination.”

“Oh, I know a little boy who’s pushing the limit,” Lisa said, wringing out her wet hair over the bath.

“Really? If only I could be him right now.”

“Why?”

Eiffel coughed and nodded towards the window. “Next year is the World’s Fair and the Paris city council has asked me to design a tower to go in that square you see out there. They have only three requirements: that it should be beautiful, ingenious and should take the breath away from everyone who sees it. Fine . . .” Eiffel let his monocle fall into his hand, closed his eyes and rubbed his pipe against his forehead. “The problem is that I just don’t have the imagination to come up with something that beautiful and ingenious. And the only thing taking away my breath is this tobacco, which isn’t anywhere near strong enough. Construction has to start in a few months, and now everyone’s just waiting for me to complete the design. But I can’t do it. They’re going to fire me and assign me to design bike racks!”

He had another coughing fit, and the red colouring climbed up his face as if he were a thermometer.

“Hogwash,” Lisa said. “Of course you can draw something beautiful and ingenious.”

“Afraid not,” Eiffel said, choking up a little. “All I can design are broad, solid and rather ugly bridges. Like this bridge your professor came to ask me about . . .”

“Yes?”

“There’s a bridge in Provence that I’ve already finished the drawings for. I was going to turn them in next week. He wanted me to adjust the plans, make the bridge a tiny little bit narrower. Something about hippopotamuses and their limousines . . .”

“Yes, yes!” Lisa cried. “Narrower so that Doctor Proctor and Juliette can get away and go to Rome and get married!”

“Yes, that’s what he said. A touching story, I must admit it choked me up a little. And I really wasn’t at all opposed to making that hideous monstrosity a little narrower. So I said yes.”

“Yippee!” Lisa exclaimed jumping up and down. “Then it’ll work! Then everything will be fine! Thank you so, so much, Mr Eiffel! Goodbye!” She jumped back into the bath.

“Wait a sec . . .” Eiffel said.

“I have to hurry to get back to my own time while there are still soap bubbles. I’m sure they’re all waiting for me.”

“Your professor didn’t go back. He wouldn’t let me change the plans for the bridge.”

“What?” Lisa gasped, her eyes wide. “Why not?”

“We shared a bottle of wine while he told me a little about what was going to happen in the future. And then he suddenly thought of something he’d forgotten. That if the bridge were narrower, the American tanks that liberated France from Hitler in World War Two wouldn’t be able to cross it. And that would be a catastrophe worse than he and Juliette not ending up together. Yes, this Hitler is going to be born very soon and as I understand it he’s going to be a horrible person. So we don’t want him to hold on to France.”

“No, obviously not,” Lisa said. “But . . . but then, well, but then everything is lost. Then Claude Cliché is going to win after all.”

“Yes, that’s what your Doctor Proctor said too,” Eiffel said, slowly nodding his head. “So we opened another bottle of wine, drank more and both got a little upset.”

“And then?” Lisa asked.

“Then I did the only thing I’m any good at,” Eiffel said. “I thought about things logically.”

“What do you mean?”

“Your professor told me that when Juliette’s great-great-great-great-grandfather, the Count of Monte Crisco, was beheaded in the French Revolution, the family fortune was inherited by Leaufat Margarine, who had a gambling addiction. He promptly gambled it all away playing Uno. But, if the Count hadn’t been beheaded, he almost certainly would have had children. And then they would have inherited the fortune instead of this drunken lout Leaufat. And then the Margarine family would still have this fortune. And then Juliette’s father wouldn’t have needed to say yes to Claude Cliché’s offer to save them from ruin by marrying his daughter. So I asked the professor why he didn’t just g

o back to the Revolution and save the Count from the guillotine. Quite logical, don’t you think?”

“Quite,” Lisa said. “But what’s a . . . uh, guillotine?”

“Oh, that,” Eiffel said eagerly. “A very clever invention that the revolutionaries used to chop the heads off of counts and barons. Well, countesses and baronesses too, for that matter. Quick and efficient, chop, chop! I have the drawings for the invention around here somewhere . . .” Eiffel pulled open one of his desk drawers.

“Oh, that’s really not necessary,” Lisa said quickly. “So that’s where Doctor Proctor went? To the French Revolution?”

“Yes, but he had to find this Count in the middle of all the chaos that was raging in Paris in 1793. So I’m not really sure exactly where he is now. Or then. Or back then. Ugh, this time-travel business is a little confusing, don’t you think?” Eiffel succumbed to another coughing fit and his eyes bulged so much it looked like they were going to pop out of his head.

Lisa looked at the soap bubbles, which were already fading away in the bath. She had to hurry if she was going to make it out of here.

“So he didn’t leave any kind of message behind that might make it easier for me to find him?” she asked.

“I’m afraid not,” Eiffel said, shaking his head sadly. “Well, after your professor thought about it a bit, he asked me if I had a postcard and a stamp with a picture of Felix Faure from 1888. Which of course I had, since it’s 1888 now and Felix Faure is the current president, right?” Eiffel laughed. “Your professor claimed that the stamp was going to be very rare and valuable someday, which is obviously completely ridiculous. Because this stamp is completely commonplace – you can find it in any house in France! But anyway I gave him the stamp and a postcard with a picture of the square you see out of the window there.”

“I knew there was something familiar about that square!” Lisa exclaimed. She thought about the picture on the postcard, how she’d thought the empty public square seemed like it was missing something. And suddenly she thought she knew what it was missing . . .

Blood on Snow: A novel

Blood on Snow: A novel Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8)

Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8) Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery Bubble in the Bathtub

Bubble in the Bathtub Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb The Bat

The Bat Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe.

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe. Silent (but Deadly) Night

Silent (but Deadly) Night Who Cut the Cheese?

Who Cut the Cheese? Headhunters

Headhunters The Jealousy Man and Other Stories

The Jealousy Man and Other Stories Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle

Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle The Thirst

The Thirst The Son

The Son The Redeemer

The Redeemer The Kingdom

The Kingdom The Snowman

The Snowman The Redbreast

The Redbreast Phantom

Phantom Macbeth

Macbeth The Leopard

The Leopard Blood on Snow

Blood on Snow Midnight Sun

Midnight Sun The Redbreast (Harry Hole)

The Redbreast (Harry Hole) The Devil's Star

The Devil's Star Cockroaches

Cockroaches The Magical Fruit

The Magical Fruit The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel

The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder The Cockroaches

The Cockroaches Knife

Knife Phantom hh-9

Phantom hh-9 The Redbreast hh-3

The Redbreast hh-3 The Redeemer hh-6

The Redeemer hh-6 The Leopard hh-8

The Leopard hh-8 The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel

The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel The Great Gold Robbery

The Great Gold Robbery Police hh-10

Police hh-10 The End of the World. Maybe

The End of the World. Maybe The Thirst: Harry Hole 11

The Thirst: Harry Hole 11 Nemesis - Harry Hole 02

Nemesis - Harry Hole 02 The Devil's star hh-5

The Devil's star hh-5 Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Time-Travel Bath Bomb