The Bat Read online

Page 15

‘Ben likes to talk a lot when he’s warmed to a topic,’ Birgitta explained. ‘He’s almost as happy talking to people as he is to his fish.’ She had worked for the last two summers as a spare hand at the aquarium and had become good friends with the watchman, who claimed he had been working at the aquarium ever since it opened.

‘It’s so peaceful here at night,’ Birgitta said. ‘So quiet. Look!’ She shone the torch on the glass wall where a black-and-yellow moray fish glided out of its cave revealing a row of small, sharp teeth. Further down the corridor she lit up two speckled stingrays slipping through the water behind the green glass with slow-motion winglike movements. ‘Isn’t that beautiful?’ she whispered with gleaming eyes. ‘It’s like ballet without the music.’

Harry felt as though he were tiptoeing through a dormitory. The only sounds were their steps and a faint but regular gurgle from the aquariums.

Birgitta stopped by one high glass wall. ‘This is the aquarium’s saltie, Matilda from Queensland,’ she said, directing the cone of light at the glass. There was a dried-out tree trunk lying on a reconstructed riverbank inside. And in the pool a floating piece of wood.

‘What’s a saltie?’ Harry asked, trying to catch sight of something living. At that moment the piece of wood opened two shimmering, green eyes. They lit up in the dark like reflectors.

‘It’s a crocodile that lives in salt water, in contrast to the freshie. Freshies live off fish and you don’t need to be afraid of them.’

‘And salties?’

‘You should definitely be afraid of them. Many so-called dangerous predators attack humans only when they feel threatened, are afraid or you’ve encroached on their territory. A saltie, however, is a simple, uncomplicated soul. It just wants your body. Several Australians are killed every year in the swamplands to the north.’

Harry leaned against the glass. ‘Doesn’t that lead to . . . a . . . er, certain antipathy? In some parts of India they wiped out the tiger under the pretext it was eating babies. Why have these man-eaters not been exterminated?’

‘Most people here have the same relaxed kind of attitude to crocodiles as they do to traffic accidents. Almost, anyway. If you want roads, you’ve got to accept deaths, right? Well, if you want crocodiles, it’s the same thing. These animals eat humans. That’s life.’

Harry shuddered. Matilda had closed her eyelids in a similar way to the headlamp covers on some models of Porsche. Not a ripple in the water betrayed the fact that the wood lying half a metre from him behind the glass was in reality more than a ton of muscle, teeth and ill temper.

‘Let’s go on,’ he suggested.

‘Here we have Mr Bean,’ Birgitta said, shining the torch on a small, light brown, flounder-like fish. ‘This is a fiddler ray, it’s what we call Alex in the bar, the man Inger called Mr Bean.’

‘Why Fiddler Ray?’

‘I don’t know. They called him that before I started there.’

‘Funny name. It obviously likes lying still on the bottom.’

‘Yes, and that’s why you’ve got to be careful when you’re in the water. It’s poisonous, you see, and it’ll sting you if you tread on it.’

They descended a staircase that wound down to one of the big tanks.

‘The tanks aren’t actually aquariums in the true sense of the word, they’ve just enclosed a part of Sydney Harbour,’ Birgitta said as they entered.

From the ceiling a greenish light fell over them in undulating stripes, and made Harry feel as if he were standing under a mirror-ball. It was only when Birgitta pointed the torch upwards that he saw they were surrounded by water on all sides. They were standing in a glass tunnel under the sea, and the light was coming from outside, filtered through the water. A huge shadow glided past them, and he instinctively recoiled.

‘Mobulidae,’ she said. ‘Devil rays.’

‘My God, it’s enormous!’ Harry breathed.

The whole skate was one single billowing movement, like a massive waterbed, and Harry felt sleepy just looking at it. Then it turned onto its side, waved to them and floated into the dark watery world like a black bed-sheet spook.

They sat on the floor and from her rucksack Birgitta took a rug, two glasses, a candle, and an unlabelled bottle of red wine. Present from a friend working at a vineyard in Hunter Valley, she said, opening it. Then they lay side by side on the rug looking up into the water.

It was like lying in a world turned upside down, like seeing into an inverted sky full of fish all the colours of the rainbow and strange creatures invented by someone with an overactive imagination. A blue, shimmering fish with an enquiring moon-face and thin, quivering ventral fins hovered in the water above them.

‘Isn’t it wonderful to see how much time they take, how apparently meaningless their activities are?’ whispered Birgitta. ‘Can you feel them slowing time down?’ She placed a cold hand on Harry’s neck and squeezed softly. ‘Can you feel your pulse almost stopping?’

Harry swallowed. ‘I don’t mind time going slowly. Not right now,’ he said. ‘Not for the next few days.’

Birgitta squeezed harder. ‘Don’t even talk about it,’ she said.

‘Sometimes I think, “Harry, you’re not so bloody stupid after all.” I notice, for example, that Andrew always talks about the Aboriginal people as “them”. That’s why I’d guessed a lot of Andrew’s story before Toowoomba told me specific details. I’d more or less surmised that Andrew hadn’t grown up with his own family, that he doesn’t belong anywhere but floats along on the surface and sees things from the outside. Like us here, observing a world which we cannot take part in. After the chat with Toowoomba I realised something else: at birth Andrew didn’t receive that gift of natural pride you have with being part of a people. That’s why he had to find his own. At first I thought he was ashamed of his brothers, but now I know he’s grappling with his own shame.’

Birgitta grunted. Harry went on.

‘Sometimes I think I’ve got something, only in the next minute to be thrown into confusion once again. I don’t like being confused; I have no tolerance for it. That’s why I wish either I didn’t have this ability to capture details, or I had a greater ability to assemble them into a picture that made some sense.’

He turned to Birgitta and buried his face in her hair.

‘It’s a bad job on God’s part to give a man with so little intelligence such a good eye for detail,’ he said, trying to place something that had the same scent as Birgitta’s hair. But it was so long ago he had forgotten what it was.

‘So what can you see?’ she asked.

‘Everyone’s trying to point my attention to something I don’t understand.’

‘Like what?’

‘I don’t know. They’re like women. They tell me stories that mean something else. What’s between the lines may be blindingly obvious, but, as I say, I don’t have the ability to see. Why can’t you women just say things as they are? You overestimate men’s ability to interpret.’

‘Is it my fault now?’ she exclaimed with a smile and smacked him. The echo rolled down the underwater tunnel.

‘Shh, don’t wake the Great White,’ said Harry.

It took Birgitta quite a while to spot that he hadn’t touched his wine glass.

‘A little glass of wine can’t hurt, can it?’ she said.

‘Yes, it can,’ Harry answered. ‘It can hurt.’ He pulled her towards him with a smile. ‘But let’s not talk about that.’ Then he kissed her, and she took a long, trembling breath, as though she had been waiting for this kiss for an eternity.

Harry woke with a start. He didn’t know where the green light in the water had come from, whether it was the moon over Sydney or searchlights on land, but now it was gone. The candle had burned out, and it was pitch black. Yet he had a feeling he was being watched. He located the torch beside Birgitta and switched it on – she was wrapped in her half of the rug, naked and with a contented expression. He shone the light on the glass.

At first he thought it was his own reflection he could see, then his eyes became accustomed to the light and he felt his heart register a last pounding beat before it froze. The Great White was beside him, watching him with cold, lifeless eyes. Harry breathed out and condensation formed on the glass in front of the pale, watery face, the apparition of a drowned man that was so large it seemed to fill the whole tank. The teeth protruded from the jaw, looking as if they had been drawn by a child, a zigzag line of triangles, white daggers, arranged at random in two gumless rows.

Then it floated up and above him, all the while with its dead eyes fixed on him, stiffened into a look of hatred, a white corpse-like body gliding past the torch beam in slow, undulating movements, seemingly never-ending.

25

Mr Bean

‘SO YOU’RE LEAVING soon?’

‘Yup.’ Harry sat with a cup of coffee in his lap, not knowing quite what to do with it. McCormack got up from his desk and started pacing by the window.

‘So you think we’re still a long way from cracking the case, do you? You think there’s some psychopath out there in the masses, a faceless murderer who kills on impulse and leaves no clues. And that we’ll have to hope and pray he makes a mistake next time he strikes?’

‘I didn’t say that, sir. I just don’t think I’ve got anything to offer here. Plus, I had a call to say they need me in Oslo.’

‘Fine. I’ll inform them you’ve acquitted yourself well here, Holy. I understand you’re being considered for promotion at home.’

‘No one said anything to me, sir.’

‘Take the rest of the day off and see some of Sydney’s sights before you go, Holy.’

‘I’ll just eliminate this Alex Tomaros from our inquiries first, sir.’

McCormack stood gazing out of the window at an overcast and stifling hot Sydney.

‘I long for home too, Holy. Across the beautiful sea.’

‘Sir?’

‘Kiwi. I’m a Kiwi, Holy. My parents came here when I was ten. Folk are nicer to each other over there. That’s how I remember it, anyway.’

‘We don’t open for several hours yet,’ said the grumpy woman at the door with a broom in her hand.

‘That’s all right. I’ve got an appointment with Mr Tomaros,’ Harry said, wondering whether she would be convinced by a Norwegian police badge. It proved to be unnecessary. She opened the door just wide enough for Harry to enter. There was a smell of stale beer and soap, and strangely enough the Albury seemed smaller now that he saw it empty and in daylight.

He found Alex Tomaros, alias Mr Bean, alias Fiddler Ray, inside his office behind the bar. Harry introduced himself.

‘How can I help you, Mr Holy?’ He spoke quickly and with an unmistakable accent, the way foreigners, even when they have lived in a country for years, often do.

‘Thank you for agreeing to meet at such short notice, Mr Tomaros. I know other officers have been here and asked you a whole load of things, so I won’t detain you any longer than necessary. I—’

‘That’s fine. As you see, I have quite a bit to do. Accounts, you know . . .’

‘I understand. From your statement I saw that you were doing accounts on the evening Inger Holter went missing. Was there anyone here with you?’

‘If you’d read my statement thoroughly I’m sure you’d have seen I was on my own. I’m always on my own . . .’ Harry studied Tomaros’s arrogant face and slavering mouth. I believe you, he thought. ‘. . . doing accounts. Completely and utterly. If I’d wanted, I could have swindled this place out of hundreds of thousands of dollars without anyone noticing a thing.’

‘Technically, then, you don’t have an alibi.’

Tomaros removed his glasses. ‘Technically, I rang my mother at two and said I’d finished and was on my way home.’

‘Technically, there’s a great deal you could have done between one, when the bar closed, and two, Mr Tomaros. Not that I’m saying you’re under suspicion or anything.’

Tomaros stared at him without blinking.

Harry flicked through his empty notepad and pretended to be looking for something.

‘Why did you ring your mother, by the way? Isn’t a bit unusual to ring someone at two o’clock in the morning with that kind of message?’

‘My mother likes to know where I am. The police have spoken to her too, so I don’t know why we have to go through this again.’

‘You’re Greek, aren’t you?’

‘I’m an Australian and have lived here for twenty years. My mother’s an Australian national now. Anything else?’ He was controlling himself well.

‘You showed a personal interest in Inger Holter. How did you react when she rejected you?’

Tomaros licked his lips, and he was about to say something but paused. The tongue appeared again. Like a snake’s, Harry thought. A poor little black snake everyone despises and believes is harmless.

‘Miss Holter and I talked about having dinner together, if that’s what you’re alluding to. She’s the only person here I’ve asked out. You can check with any of the others. Cathrine and Birgitta, for example. I set great store by having a good relationship with my employees.’

‘Your employees?’

‘Well, technically, I’m—’

‘The bar manager. Well, Mr Bar Manager, how did you like her boyfriend making an appearance here?’

Tomaros’s glasses had started misting up. ‘Inger had a good relationship with many of the customers, so it was impossible for me to know which of them was her boyfriend. So she had a boyfriend? Good for her . . .’

Harry didn’t need to be a psychologist to see through Tomaros’s attempt to sound indifferent.

‘You had no idea, then, who she was on intimate terms with, Tomaros?’

He rolled his shoulders. ‘There was the clown, of course, but his inclinations were elsewhere . . .’

‘The clown?’

‘Otto Rechtnagel, a regular here. She used to give him food for—’

‘The dog!’ Harry shouted. Tomaros jumped in his chair.

Harry got up and smacked a fist into his palm.

‘That’s it! Otto was given a bag yesterday. It was leftovers for the dog! I remember now, he said he had a dog. Inger told Birgitta she was taking leftovers for the dog on the evening she went missing, and all the time we assumed they were for the landlord’s dog. But the Tasmanian Devil’s a vegetarian. Do you know what the leftovers were? Do you know where Rechtnagel lives?’

‘Good God, how should I know?’ Tomaros said, horrified. He had pushed his chair right back against the bookcase.

‘OK, listen to me. Keep quiet about this conversation, don’t even mention it to your beloved mother, otherwise I’ll be back to cut your head off. Do you understand, Mr Bea— Mr Tomaros?’

Alex Tomaros just nodded.

‘And now I need to make a phone call.’

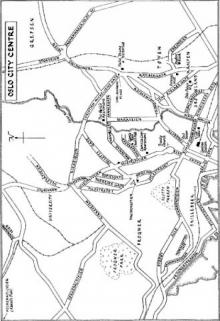

The fan creaked abjectly, but no one in the room noticed. Everyone’s attention was focused on Yong, who had placed a transparency showing a map of Australia on the overhead projector. On the map he had put small red dots with dates next to them.

‘These are the times and places of the rapes and murders which we feel our man is responsible for,’ he said. ‘We’ve tried before to find some geographical or temporal pattern without any success. Now it looks as if Harry’s found one for us.’

Yong put another transparency over the first with the same map. This one had blue dots, which covered almost all the red ones beneath.

‘What’s this?’ Watkins asked tetchily.

‘This is taken from the list of shows performed by the Australian Travelling Show Park, a circus, and indicates where they were on the relevant dates.’

The fan continued its lament, but otherwise the conference room was utterly still.

‘Holy Dooley, we’ve got ’im!’ Lebie shouted.

‘The chances of this being a coincidence are, statistically speaking, about one in four million,’ Yong smiled.

‘Wait, wait, who is it we’re looking for now?’ Watkins interjected.

‘We’re looking for this man,’ Yong said, placing a third transparency on the overhead. Two sad eyes set in a pale, slightly bloated face with a tentative smile looked at them from the screen. ‘Harry can tell you who this is.’

Harry got up.

‘This is Otto Rechtnagel, a professional clown, forty-two years old, who has been on the road with the Australian Travelling Show Park for the last ten years. When the circus isn’t working he lives alone in Sydney and performs freelance. At the moment he’s started up a small troupe giving shows in town. He’s got a clean record as far as we can see, has never been in the spotlight in connection with any sexual offences and is considered a convivial, quiet fellow, though somewhat eccentric. The crunch is that he knew the deceased, he was a regular at the bar where Inger Holter worked and they had become good friends over time. She was probably on her way to Rechtnagel’s the night she was killed. With food for his dog.’

‘Food for his dog?’ Lebie laughed. ‘At half past one in the morning? I think our clown had something else on his mind.’

‘And right there you’ve put your finger on the bizarre side of the case,’ Harry said. ‘Otto Rechtnagel has maintained a facade as a hundred per cent, card-carrying homosexual since the age of ten.’

This information occasioned mumbling round the table.

Watkins groaned. ‘Do you believe that a homosexual man like this could have killed seven women and raped six times as many?’

McCormack had entered the room. He had been briefed. ‘If you’ve been a happy homo with exclusively homo friends for the whole of your life, it’s perhaps not so surprising that you become anxious the day you discover that the sight of a shapely pair of tits makes John Thomas twitch. Christ, we’re living in Sydney, the only town in the world where people are closet heteros.’

Blood on Snow: A novel

Blood on Snow: A novel Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8)

Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8) Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery Bubble in the Bathtub

Bubble in the Bathtub Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb The Bat

The Bat Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe.

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe. Silent (but Deadly) Night

Silent (but Deadly) Night Who Cut the Cheese?

Who Cut the Cheese? Headhunters

Headhunters The Jealousy Man and Other Stories

The Jealousy Man and Other Stories Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle

Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle The Thirst

The Thirst The Son

The Son The Redeemer

The Redeemer The Kingdom

The Kingdom The Snowman

The Snowman The Redbreast

The Redbreast Phantom

Phantom Macbeth

Macbeth The Leopard

The Leopard Blood on Snow

Blood on Snow Midnight Sun

Midnight Sun The Redbreast (Harry Hole)

The Redbreast (Harry Hole) The Devil's Star

The Devil's Star Cockroaches

Cockroaches The Magical Fruit

The Magical Fruit The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel

The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder The Cockroaches

The Cockroaches Knife

Knife Phantom hh-9

Phantom hh-9 The Redbreast hh-3

The Redbreast hh-3 The Redeemer hh-6

The Redeemer hh-6 The Leopard hh-8

The Leopard hh-8 The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel

The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel The Great Gold Robbery

The Great Gold Robbery Police hh-10

Police hh-10 The End of the World. Maybe

The End of the World. Maybe The Thirst: Harry Hole 11

The Thirst: Harry Hole 11 Nemesis - Harry Hole 02

Nemesis - Harry Hole 02 The Devil's star hh-5

The Devil's star hh-5 Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Time-Travel Bath Bomb