The Thirst: Harry Hole 11 Read online

Page 16

There was a buzz and a crackle and voices relaying short messages before disappearing again. The sounds of the city conveyed through a police radio soothed him more than music.

Truls looked at the glove compartment he’d just opened. The binoculars were tucked behind his service pistol. He had promised himself that he was going to stop. That it was time, that he didn’t need this any more, not now he’d found out there were other fish in the sea. OK. Monkfish, sculpins and weevers. Truls heard himself grunt. It was his laugh that had earned him the nickname Beavis. That, and his heavy lower jaw. And there she was, up there, imprisoned in that oversized, overpriced house with a terrace that Truls had helped construct, and where he had buried the corpse of a drug dealer in wet cement, a corpse that only Truls knew about, and which had never given him so much as one sleepless night.

A scraping sound on the radio. The voice from Emergency Control.

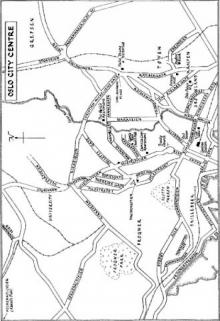

‘Have we got any cars near Hovseter?’

‘Car 31, in Skøyen.’

‘Hovseterveien 44, doorway B. We got a pretty hysterical resident saying there’s a madman in the stairwell assaulting a woman there, but that they daren’t intervene because he’s smashed the light on the stairs and it’s pitch-black.’

‘Assaulting with a weapon?’

‘They don’t know. They say they saw him bite her before it went dark. The caller’s name was Amundsen.’

Truls reacted instantly and pressed the ‘speak’ button on the radio. ‘Detective Constable Truls Berntsen here, I’m closer, I’ll take it.’

He had already started the engine, and revved it hard as he pulled out onto the road, hearing a car coming round the bend behind him blow its horn angrily.

‘Copy,’ Emergency Control said. ‘And where are you, Berntsen?’

‘Just round the corner, I said. 31, I want you as backup, so wait if you get there first. Suspect that the assailant is armed. Repeat, armed.’

Saturday night, almost no traffic. If he drove through the Opera Tunnel at full speed, cutting straight through the centre beneath the fjord, he wouldn’t be more than seven or eight minutes behind car 31. Those minutes could, of course, be critical, both for the victim and for the perpetrator to get away, but Detective Constable Truls Berntsen could also be the officer who arrested the vampirist. And who knew what VG would be willing to pay for a report from the first man on the scene. He blew the car’s horn repeatedly and a Volvo swerved out of his way. Dual carriageway now. Three lanes. Foot on the floor. His heart was pounding against his ribs. A speed camera in the tunnel flashed. Police officer on duty, a licence to tell everyone in this whole damn city to fuck off. On duty. His blood was pulsing through his veins, brilliant, as if he was about to get a hard-on.

‘Ace of space!’ Truls roared. ‘Ace of space!’

‘Yes, we’re car 31. We’ve been waiting!’ The man and woman were standing behind the patrol car parked in front of doorway B.

‘Slow lorry that wouldn’t let me pass,’ Truls said, checking that his pistol was loaded and the cartridge full. ‘Heard anything?’

‘It’s all quiet in there. No one’s entered or left.’

‘Let’s go.’ Truls pointed to the male officer. ‘You come with me, and bring a torch.’ He nodded to the woman. ‘You stay here.’

The two men walked up to the entrance. Truls peered through the window at the darkened stairwell. He pressed the button beside the name Amundsen.

‘Yes?’ a voice whispered.

‘Police. Have you heard anything since you called?’

‘No, but he could still be out there.’

‘OK. Open the door.’

The lock clicked and Truls pulled the door open. ‘You go first with the torch.’

Truls heard the officer swallow. ‘I thought you said backup, not up front.’

‘Just be grateful you’re not here on your own,’ Truls whispered. ‘Come on.’

Rakel looked at Harry.

Two murders. A new serial killer. His type of hunt.

He was sitting there eating, making out that he was following the conversation around the table, was polite towards Helga, listened with apparent interest to Oleg. Perhaps she was wrong, perhaps he really was interested. Perhaps he wasn’t completely enchained by it after all, perhaps he had changed.

‘Gun licences are pointless when people will soon be able to buy a 3D printer and make their own pistols,’ Oleg said.

‘I thought 3D printers could only make things out of plastic?’ Harry said.

‘Home printers, yes. But plastic is durable enough if you just want a weapon and you’re only going to use it once to murder someone.’ Oleg leaned across the dining table. ‘You don’t even need an original pistol as the template, you just borrow one for five minutes, dismantle it, take wax copies of the pieces, then use those to make a 3D model that you feed into the computer that controls the printer. Once the murder has been committed, you just melt the whole plastic pistol down. And if anyone did work out that that was the murder weapon, it wouldn’t be registered to anyone.’

‘Hm. But the pistol could still be traced back to the printer that produced it. Forensics can already do that with inkjet printers.’

Rakel looked at Helga, who was looking rather lost.

‘Boys …’ Rakel said.

‘Whatever,’ Oleg said. ‘It’s really crazy – they can make practically anything. So far there are just over two thousand 3D printers in Norway, but imagine when everyone’s got one, when terrorists can 3D-print a hydrogen bomb.’

‘Boys, can’t we talk about something more pleasant?’ Rakel said, feeling strangely breathless. ‘Something a bit more cultured, just for once, seeing as we’ve got a guest?’

Oleg and Harry turned towards Helga, who smiled and shrugged, as if to say that she was fine with anything.

‘OK,’ Oleg said. ‘What about Shakespeare?’

‘That sounds better,’ Rakel said, looking at her son suspiciously as she passed the potatoes to Helga.

‘OK, Ståle Aune and Othello syndrome,’ Oleg said. ‘I haven’t told you that Jesus and I recorded the entire lecture. I was wearing a hidden microphone and transmitter under my shirt, and Jesus was in the next room recording it. Do you think Ståle would be OK if we uploaded it to the Net? What do you think, Harry?’

Harry didn’t answer. Rakel studied him. Was he drifting away again?’

‘Harry?’ she said.

‘Well, obviously I can’t answer that,’ he said, looking down at his plate. ‘But why didn’t you just record it on your phone? It isn’t forbidden to record lectures for private use.’

‘They’re practising,’ Helga said.

The others turned towards her.

‘Jesus and Oleg dream of working as undercover agents.’

‘Wine, Helga?’ Rakel picked up the bottle.

‘Thanks. But aren’t you having any?’

‘I’ve taken a headache pill,’ Rakel said. ‘And Harry doesn’t drink.’

‘I’m a so-called alcoholic,’ Harry said. ‘Which is a shame, because that’s supposed to be a really good wine.’

Rakel saw Helga’s cheeks burn, and hurried to ask: ‘So Ståle’s teaching you about Shakespeare?’

‘Yes and no,’ Oleg said. ‘Othello syndrome implies that jealousy is the main reason for the murders in the play, but that isn’t true. Helga and I read Othello yesterday—’

‘You read it together?’ Rakel put her hand on Harry’s arm. ‘Isn’t that sweet?’

Oleg looked up at the ceiling. ‘Either way, my interpretation is that the real, underlying cause of all the murders isn’t jealousy but a humiliated man’s envy and ambition. In other words, Iago. Othello is just a puppet. The play ought to be called Iago, not Othello.’

‘And do you agree with that, Helga?’ Rakel liked the slim, slightly anaemic, well-mannered girl, and she seemed to have found her feet pretty quickly.

‘I like Othello as the title. And maybe there isn’t a deep-seated reaso

n. Maybe it’s like Othello himself says. That the full moon is the real cause, because it drives men mad.’

‘No reason,’ Harry declaimed solemnly in English. ‘I just like doing things like that.’

‘Impressive, Harry,’ Rakel said. ‘You can quote Shakespeare.’

‘Walter Hill,’ Harry said. ‘The Warriors, 1979.’

‘Yeah,’ Oleg laughed. ‘Best gang film ever.’

Rakel and Helga laughed. Harry raised his glass of water and looked across the table at Rakel. Smiled. Laughter round the family dinner table. And she thought that he was here now, he was with them. She tried to hold on to his gaze, hold on to him. But imperceptibly, as the sea turns from green to blue, it happened. His eyes turned inward again. And she knew that even before the laughter had died out, he was on his way again, into the darkness, away from them.

Truls walked up the stairs in the dark, crouching with his pistol behind the big, uniformed police officer with the torch. The silence was only broken by a ticking sound, like a clock somewhere further up inside the building. The cone of light from the torch seemed to push the darkness ahead of them, making it denser, more compact, like the snow Truls and Mikael used to shovel for pensioners in Manglerud. Afterwards they would snatch the hundred-krone note from gnarled, trembling hands, and say they would come back with the change. If they ever did wait for them, they were waiting still.

Something crunched beneath their feet.

Truls grabbed the back of the policeman’s jacket, and he stopped and pointed the torch at the floor. Splinters of glass sparkled, and between them Truls could see indistinct footprints in what he was fairly sure was blood. The heel and front of the sole were clearly divided, but he thought the print was too big to be a woman’s. The prints were pointing down the stairs, and he was sure he would have seen them if there had been any further down. The ticking sound had got louder.

Truls gestured to the policeman to go on. He looked at the stairs, saw that the bloody prints were getting clearer. Looked up the stairs. Stopped and raised his pistol. Let the policeman carry on. Truls had seen something. Something that had fallen through the light. Something that sparkled. Something red. It wasn’t ticking they had heard, it was the sound of blood dripping and hitting the stairs.

‘Shine the torch upward,’ he said.

The police officer stopped, turned round, and for a moment looked surprised that the colleague whom he had thought was right behind him had stopped a few steps below and was looking up at the ceiling. But he did as Truls said.

‘Oh my God …’ he whispered.

‘Amen,’ Truls said.

There was a woman hanging from the wall above them.

Her checked skirt had been pulled up, revealing the edge of her white knickers. On one thigh, level with the policeman’s head, blood was dripping from a large wound. It ran down her leg, into her shoe. The shoe was evidently full, because the blood was running down the outside and gathering in drops at the point of the shoe, then falling to join a red puddle on the stairs. Her arms were pulled up above her lolling head. Her wrists were tied with a peculiar set of cuffs which had been hooked over the lamp bracket. Whoever had put her there had to be strong. Her hair was covering her face and neck, so Truls couldn’t see if there was a bite mark, but the amount of blood in the puddle and the terrible dripping told him that she was empty, dry.

Truls looked hard at her. Memorised every detail. She looked like a painting. He would use that expression when he spoke to Mona Daa. Like a painting hung on the wall.

A door opened slightly on the landing above them. A pale face peered out. ‘Has he gone?’

‘Looks like it. Amundsen?’

‘Yes.’

Light streamed out when the door on the other side of the hallway opened. They heard a gasp of horror.

An elderly man stumbled out while a woman who was presumably his wife stayed behind and looked out anxiously from the doorway. ‘That was the devil himself,’ the man said. ‘Look what he’s done.’

‘Please, don’t come any closer,’ Truls said. ‘This is a murder scene. Does anyone know where the perpetrator went?’

‘If we’d known he was gone, we’d have come out to see if there was anything we could do,’ the old man said. ‘But we did see a man from the living-room window. He left the building and headed off towards the metro. We don’t know if it was him though. Because he was walking so calmly.’

‘How long ago was this?’

‘Quarter of an hour, at most.’

‘What did he look like?’

‘Now you’re asking …’ He turned to his wife for help.

‘Ordinary,’ she said.

‘Yes,’ the man agreed. ‘Neither tall nor short. Neither fair nor dark hair. A suit.’

‘Grey,’ his wife added.

Truls nodded to the policeman, who understood the signal and began talking into the radio that was clipped to the top pocket of his jacket. ‘Request assistance to Hovseterveien 44. Suspect observed heading on foot towards the metro, fifteen minutes ago. Approximately 1 metre 75, possibly ethnic Norwegian, grey suit.’

Fru Amundsen had come out from behind the door. She seemed even less steady on her feet than her husband, and her slippers dragged on the floor as she pointed a trembling finger at the woman on the wall. She reminded Truls of one of those pensioners they used to clear snow for. He raised his voice: ‘I said, don’t come any closer!’

‘But—’ the woman began.

‘Inside! Murder scenes mustn’t be contaminated before Forensics gets here, we’ll ring on the door if we have any questions.’

‘But … but she’s not dead.’

Truls turned round. In the light from the open door, he saw the woman’s right foot quiver, as if it was cramping. And the thought popped into his head before he could stop it. That she was infected. She had become a vampire. And now she was waking up.

12

SATURDAY NIGHT

THERE WAS A loud noise of metal on metal as the bar carrying the weights hit the cradle above the narrow bench. Some people would think it a terrible sound, but for Mona Daa it was like bells chiming. And she wasn’t bothering anyone else either, she was on her own at Gain Gym. They’d switched to twenty-four-hour opening six months ago, presumably inspired by gyms in New York and Los Angeles, but Mona still hadn’t seen anyone else exercising there after midnight. Norwegians simply didn’t work enough hours for it to be a problem finding time for the gym during the day. She was the exception. She wanted to be the exception. A mutant. Because it was like evolution, it was the exceptions who drove the world forward. Who perfected things.

Her phone rang, and she got up from the bench.

It was Nora. Mona put her earphone in and took the call.

‘You’re at the gym, bitch,’ her friend groaned.

‘I haven’t been here long.’

‘You’re lying, I can see that you’ve been there for two hours.’

Mona, Nora and a few of their other friends from college could find each other using the GPS on their mobiles. They’d activated a service that allowed them to voluntarily track the others’ phones. It was both sociable and reassuring. But Mona couldn’t help thinking that it felt a bit claustrophobic at times. Professional sisterhood was all well and good, but they didn’t have to follow each other about like fourteen-year-olds going to the toilet together. It was high time they realised that the world was full of career opportunities for intelligent young women, and that the only thing holding them back was their own lack of courage and ambition, ambition to make a difference, not just get the others’ validation of their own smartness.

‘I hate you just a tiny bit when I think of all the calories that are falling off you right now,’ Nora said. ‘While I’m sitting here on my fat arse consoling myself with another pina colada. Listen …’

Mona felt like pulling the earphone out as the sound of drawn-out slurping through a straw battered her eardrum. Nora believed that a pina colada was

the only antidote to premature autumn depression.

‘Did you actually want to talk about anything, Nora? I’m in the middle of—’

‘Yep,’ Nora said. ‘Work.’

Nora and Mona had been at the College of Journalism together. A few years ago the college had had stricter entrance requirements than any other higher education establishment in Norway, and it had seemed as if every other clever little boy or girl’s dream was to get their own newspaper column or a job on television. That had certainly been the case for Nora and Mona. Cancer research and running the country were for people who weren’t quite as bright. But Mona had noticed that the College of Journalism now had competition from all the local high schools that were using their state funding to offer Norwegian youngsters popular courses in journalism, film, music and beauty therapy, with no consideration of the kind of qualifications the country lacked and actively needed. Which meant that the richest country in the world had to import those skills while the nation’s carefree, unemployed, film-studying sons and daughters were left sitting at home with their drinking straws stuck deep in the state’s milkshake while they watched – and, if they could be bothered, criticised – films made abroad. Another reason for the falling entrance requirements was of course that the boys and girls had discovered the blog market and no longer needed to work hard for the grades with which to achieve the same level of attention offered by the more traditional route of television and the newspapers. Mona had written about this, about the fact that the media no longer demanded professional qualifications from its journalists, with the result that aspiring reporters no longer made the effort to acquire them. The new media environment, with its increasingly banal focus on celebrity, had reduced the role of journalists to that of the town gossip. Mona had used her own newspaper, the biggest in Norway, as an example. The article never got published. ‘Too long,’ the features editor had said, referring her to the magazine editor. ‘Well, if there’s one thing the so-called critical press doesn’t like, it’s being criticised,’ as one more positively inclined colleague explained. But Mona had a feeling that the magazine editor hit the nail on the head when she said: ‘But, Mona, you haven’t got any quotes from celebrities here.’

Blood on Snow: A novel

Blood on Snow: A novel Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8)

Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8) Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery Bubble in the Bathtub

Bubble in the Bathtub Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb The Bat

The Bat Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe.

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe. Silent (but Deadly) Night

Silent (but Deadly) Night Who Cut the Cheese?

Who Cut the Cheese? Headhunters

Headhunters The Jealousy Man and Other Stories

The Jealousy Man and Other Stories Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle

Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle The Thirst

The Thirst The Son

The Son The Redeemer

The Redeemer The Kingdom

The Kingdom The Snowman

The Snowman The Redbreast

The Redbreast Phantom

Phantom Macbeth

Macbeth The Leopard

The Leopard Blood on Snow

Blood on Snow Midnight Sun

Midnight Sun The Redbreast (Harry Hole)

The Redbreast (Harry Hole) The Devil's Star

The Devil's Star Cockroaches

Cockroaches The Magical Fruit

The Magical Fruit The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel

The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder The Cockroaches

The Cockroaches Knife

Knife Phantom hh-9

Phantom hh-9 The Redbreast hh-3

The Redbreast hh-3 The Redeemer hh-6

The Redeemer hh-6 The Leopard hh-8

The Leopard hh-8 The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel

The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel The Great Gold Robbery

The Great Gold Robbery Police hh-10

Police hh-10 The End of the World. Maybe

The End of the World. Maybe The Thirst: Harry Hole 11

The Thirst: Harry Hole 11 Nemesis - Harry Hole 02

Nemesis - Harry Hole 02 The Devil's star hh-5

The Devil's star hh-5 Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Time-Travel Bath Bomb