The Redbreast Read online

Page 26

‘It’s practically on the way.’

‘You also live in Holmenkollen?’

‘Close by. Or quite close by. Bislett.’

She laughed.

‘On the other side of the city then. I know what you’re after.’

Harry smiled sheepishly. She put a hand on his arm. ‘You need someone to push the car, don’t you?’

‘Looks like he’s gone, Helge,’ Ellen said.

She stood by the window with her coat on, peeping out between the curtains. The street below was empty; the taxi which had been waiting there had gone off with three high-spirited party girls. Helge didn’t answer. The one-winged bird blinked twice and scratched its stomach with a foot.

She tried Harry’s mobile once again, but the same woman’s voice repeated that the phone was switched off or was in an area with poor coverage.

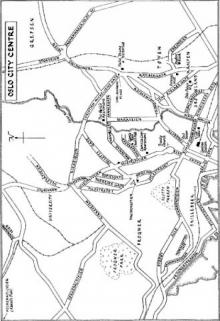

Then Ellen put the cloth over the cage, said goodnight, turned off the light and let herself out. Jens Bjelkes gate was still deserted as she hurried towards Thorvald Meyers gate, which she knew would be teeming with people at this time on a Saturday night. Outside Fru Hagen restaurant she nodded to a couple of people she must have exchanged a few words with one damp evening here in Grünerløkka’s well-lit streets. She suddenly remembered she had promised to buy Kim some cigarettes and turned to go down to the 7-Eleven in Markveien. She saw a new face she vaguely recognised and automatically smiled when she saw him looking at her.

In the 7-Eleven she paused and tried to recall whether Kim smoked Camel or Camel Lights, realising how little time they had spent together. And how much they still had to learn about each other. And that for the first time in her life it didn’t frighten her, but it was something she was looking forward to. She was so utterly happy. The thought of him lying naked in bed, three blocks away from where she was standing filled her with dull, delicious cravings. She opted for Camel, waited impatiently to be served. Outside in the street, she opted for the short cut along the Akerselva.

It struck her how little distance there was between a seething mass of people and total desolation in a large city. Suddenly all she could hear was the gurgle of the river and the sound of snow groaning beneath her boots. And it was too late to rue taking the short cut when she became aware that it was not only her own steps she could hear. Now she could hear breathing too, heavy, panting. Frightened and angry, Ellen thought that, no, she knew, at that moment her life was in danger. She didn’t turn, she simply started to run. The steps behind her immediately fell into the same tempo. She tried to run calmly, tried not to panic or run with flailing arms and legs. Don’t run like an old woman, she thought, and her hand moved for the gas spray in her coat pocket, but the steps behind her were relentless, coming ever closer. She thought that if she could reach the single cone of light on the path, she would be saved. She knew it wasn’t true. She was directly under the light when the first blow hit her shoulder and knocked her sideways into the snow-drift. The second blow paralysed her arm and the gas spray slipped out of her unfeeling hand. The third smashed her left kneecap; the pain obstructed the scream muted deep in her throat and caused her veins to bulge out in the winter-pale skin of her neck. She saw him raise the wooden baseball bat in the yellow street light. She recognised him now, the same man she had seen turn round outside Fru Hagen. The police-woman in her noticed that he was wearing a short green jacket, black boots and a black combat cap. The first blow to the head destroyed the optic nerve and now all she saw was the pitch black night.

Forty per cent of hedge sparrows survive, she thought. I’ll get through this winter.

Her fingers fumbled in the snow for something to hold on to. The second blow hit her on the back of the head.

There’s not long to go now, she thought. I’ll survive this winter.

Harry pulled up by the drive to Rakel Fauke’s house in Holmenkollveien. The white moonlight lent her skin an unreal, wan sheen and even in the semi-darkness inside the car he could see from her eyes that she was tired.

‘So that was that,’ Rakel said.

‘That was that,’ Harry said.

‘I would like to invite you up, but . . .’

Harry laughed. ‘I assume Oleg would not appreciate that.’

‘Oleg is sleeping sweetly, but I was thinking of his babysitter.’

‘Babysitter?’

‘Oleg’s babysitter is the daughter of someone in POT. Please don’t misunderstand me, but I don’t want any rumours at work.’

Harry stared at the instruments on the dashboard. The glass over the speedometer had cracked and he suspected that the fuse for the oil lamp had gone.

‘Is Oleg your child?’

‘Yes, what did you think?’

‘Well, I may have thought you were talking about your partner.’

‘What partner?’

The cigarette lighter must have been either thrown out of the window or stolen along with the radio.

‘I had Oleg when I was in Moscow,’ she said. ‘His father and I lived together for two years.’

‘What happened?’

She shrugged.

‘Nothing happened. We simply fell out of love. And I came back to Oslo.’

‘So you are . . .’

‘A single mum. What about you?’

‘Single. Only single.’

‘Before you began with us, someone mentioned something about you and the girl you shared an office with in Crime Squad.’

‘Ellen? No. We just got on well. Get on well. She still helps me out now and then.’

‘What with?’

‘The case I’m working on.’

‘Oh, I see, the case.’

She looked at her watch again. ‘Shall I help you to get the door open?’ Harry asked.

She smiled, shook her head and gave it a shove with her shoulder. The door squealed on its hinges as it swung open.

The Holmenkollen slopes were quiet, except for a gentle whistling in the fir trees. She placed a foot in the snow outside.

‘Goodnight, Harry.’

‘Just one thing.’

‘Yes?’

‘When I came here last time, why didn’t you ask me what I wanted from your father?’

‘Professional habit. I don’t ask about cases I’m not involved in.’

‘Aren’t you curious anyway?’

‘I’m always curious. I just don’t ask. What’s it about?’

‘I’m looking for an ex-soldier your father may have known at the Eastern Front. This particular man has bought a Märklin rifle. By the way, your father didn’t give the impression of being at all bitter when I talked to him.’

‘The writing project seems to have excited him. I’m surprised myself.’

‘Perhaps one day you’ll get closer again?’

‘Perhaps,’ she said.

Their eyes met, hooked on to each other almost and couldn’t let go. ‘Are we flirting now?’ she asked. ‘Highly improbable.’

He could see her laughing eyes long after he had parked illegally in Bislett, chased the monster back under the bed and fallen asleep without noticing the little red flashing light on the answerphone.

Sverre Olsen quietly closed the door behind him, took off his shoes and crept up the stairs. He skipped the step he knew would creak, but he knew this was a waste of effort.

‘Sverre?’

The shout came from the open bedroom door. ‘Yes, Mum?’

‘Where have you been?’

‘Just out, Mum. I’m going to bed now.’

He closed his ears to her words; he knew more or less what they would be. They fell like slushy sleet and were gone as soon as they hit the ground. Then he closed the door to his room and was alone. He lay down on the bed, stared at the ceiling and went through what had happened. It was like a film. He scrunched up his eyes, tried to shut it out, but the film continued to run.

He had no idea who she was. As arranged, the Prince had met him in Schous plass and they had driven to the street where she lived. T

hey had parked so that they weren’t visible from her flat, but they would be able to see her if she left the building. He had said it could take all night, told him to relax, put on that bloody nigger music and lowered the back of his seat. But the front door had opened after just half an hour and the Prince had said, ‘That’s her.’

Sverre had loped after her, but he didn’t catch up until they were in the dark street and there were too many people around them. She had suddenly turned and looked straight at him. For a moment he was sure he had been sussed, that she had seen the baseball bat up his sleeve sticking out over his jacket collar. He had been so frightened that he had not been able to control the twitches in his face, but later when she had run out of 7-Eleven, the terror had turned into anger. He remembered, and yet didn’t remember, details from when they were under the light on the path. He knew what had happened, but it was as if fragments had been removed, like in one of those quiz games on TV where you are given pieces of a picture and you have to guess what the picture is.

He opened his eyes again. Stared at the bulging plasterboard on the ceiling. When he had the money, he would get a builder to fix the leak Mum had been nagging him about for so long. He tried to think about roof repairs, but he knew it was because he was attempting to drive the other thoughts away. He knew something was wrong. It had been different this time. Not like with slit-eyes at Dennis Kebab. This girl had been a normal Norwegian woman. Short brown hair, blue eyes. She could have been his sister. He tried to repeat to himself what the Prince had instilled in him: he was a soldier, it was for the Cause.

He looked at the picture he had pinned on the wall under the flag with the swastika on. It was of the Reichsführer-SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei Heinrich Himmler speaking on the rostrum when he was in Oslo in 1941. He was talking to the Norwegian volunteers taking their oaths for the Waffen SS. Green uniform. The initials SS on the collar. Vidkun Quisling in the background. Himmler. An honourable death, 23 May 1945. Suicide.

‘Fuck!’

Sverre placed his feet on the floor, stood up and began to pace restlessly.

He stopped in front of the mirror by the door. Clutched his head. Then he searched through his jacket pockets. Damn, what had happened to his combat cap? For a moment, panic seized him as he wondered if he might have left it beside her in the snow, but then he remembered he had been wearing it when he went back to the Prince’s car. He breathed out.

He had got rid of the baseball bat, as the Prince had said. Wiped off the fingerprints and thrown it in the Akerselva. Now it was just a question of lying low and waiting to see what transpired. The Prince had said he would sort everything out, as he had done before. Sverre didn’t know where the Prince worked, but it was obvious he had good connections with the police. He undressed in front of the mirror. His tattoos were a grey colour in the moonlight as it shone in between the curtains. He fingered the Iron Cross hanging around his neck.

‘You whore,’ he mumbled. ‘You fucking commie whore.’

When he finally fell asleep, it had already begun to cloud over in the east.

51

Hamburg. 30 June 1944.

MY DEAREST BELOVED HELENA,

I love you more than I love myself. You know that now. Even though we had only a short time together, and you have a long and happy life in front of you (I know you will have!), I hope you will never forget me completely. It is evening here. I’m sitting in sleeping quarters by the harbour in Hamburg and the bombs are falling outside. I’m alone. The others are sheltering in bunkers and cellars. There’s no electricity, but the raging fires outside give more than enough light to write by.

We had to get off the train before arriving in Hamburg as the railway tracks had been bombed the night before. We were loaded on to trucks and taken to town. It was a terrible sight that met us. Every second house seemed to be in ruins, dogs slunk alongside the smoking debris and everywhere I saw emaciated children in rags staring at the trucks with their large vacant eyes. I travelled through Hamburg on my way to Sennheim only two years ago, but now it is hardly recognisable. At that time I thought the Elbe was the most beautiful river I had seen, but now bits of planks and the flotsam from wrecked shipping drift past in the filthy brown water, and I heard someone say that it has been contaminated by all the dead bodies floating in it. People were also talking about more night-time bombing raids and getting out of the city by any means possible. My plan is to take the train to Copenhagen tonight, but the railway lines to the north have also been bombed.

I apologise for my awful German. As you can see, my hand is a bit uncertain too, but it’s because the bombs are making the whole house shake. And not because I’m afraid. What should I be afraid of ? From where I’m sitting I am witness to a phenomenon I’ve heard about, but I’ve never seen – a firestorm. The flames on the other side of the harbour seem to be sucking everything in. I can see loose timber and whole lead roofs taking off and flying into the flames. And the sea – it’s boiling! Steam is rising up from under the bridges over there. If some poor soul were to try jumping into the water to escape the bombs, they would be fried alive. I opened the windows and it felt as if the air had been deprived of oxygen. And then I heard the roar – it’s as if someone is standing in the flames shouting, ‘More, more, more.’ It is uncanny and frightening, yes, but also strangely attractive.

My heart is so full of love that I feel invulnerable – thanks to you, Helena. If one day you should have children (I know you want them and I want you to have them) I want you to tell them the stories about me. Tell them as fairy tales, for that is what they are – true fairy tales. I have decided to go out into the night to see what I will find, who I will meet. I’ll leave this letter on the table in my metal canteen. I’ve scratched your name and address into it with my bayonet so that those who find it will know what to do.

Your beloved Uriah.

Part Five

SEVEN DAYS

52

Jens Bjelkes Gate. 12 March 2000.

‘HI, THIS IS ELLEN AND HELGE’S ANSWERPHONE. PLEASE leave a message.’

‘Hi Ellen, this is Harry. As you can hear, I’ve been drinking and I apologise. Really. But if I were sober, I probably wouldn’t be phoning you now. You know that, I’m sure. I went to the crime scene today. You were lying on your back in the snow by a path along the Akerselva. You were found by a young couple on the way to a dance at the Blå just after midnight. Cause of death: serious injuries to the front part of the brain as a result of violent blows from a blunt instrument. You had also been hit on the back of the head and received three fractures to the cranium as well as a smashed left kneecap and signs of a blow to the right shoulder. We assume that it was the same instrument which caused all the injuries. Doctor Blix puts the time of death between eleven and twelve at night.You seemed . . . I . . . Wait a moment.

‘Sorry. Right. The Crime Scene Unit found around twenty different types of boot print in the snow on the path and a couple in the snow beside you, but the latter had been kicked to pieces, possibly with the intention of removing clues. No witnesses have come forward so far, but we’re doing the usual rounds of the neighbourhood. Several houses overlook the path, so Kripos think there’s a chance that someone saw something. Personally, I think the chances are negligible. You see, there was a repeat of The Robinson Expedition on Swedish TV between 11.15 and 12.15. Joke. I’m trying to be funny, can you hear that? Oh, yes, we found a black cap a few metres away from where you were lying. There were bloodstains on it. If it is your blood, the cap may, ergo, belong to the murderer. We’ve sent the blood for analysis, and the cap is at the forensics lab where they are checking it for hair and skin particles. If the guy isn’t losing hair, I hope he’s got dandruff. Ha, ha. You haven’t forgotten Ekman and Friesen, have you? I haven’t got any more clues for you yet, but let me know if you come up with anything. Was there anything else? Yes, there was. Helge has found a new home with me. I know this is a change for the worse, but it is for all of us, Ellen.

With the possible exception of you. Now I’m going to have another drink and reflect on precisely that.’

53

Jens Bjelkes Gate. 13 March 2000.

‘HI, THIS IS ELLEN AND HELGE’S ANSWERPHONE. PLEASE leave a message.’

‘Hi, this is Harry again. I didn’t go to work today, but at any rate I called Doctor Blix. I’m happy to be able to tell you that you were not sexually assaulted and that, as far as we’ve been able to establish, all your earthly goods were untouched. This means that we do not have a motive, although there can be reasons for him not completing what he had set out to do. Or why he couldn’t bring himself to do it. Today two witnesses reported seeing you outside Fru Hagen. A payment from your card was registered at 22.55 at the 7-Eleven in Markveien. Your pal Kim has been at the station for questioning all day. He said you were on your way up to his and he had asked you to buy some cigarettes for him. One of the Kripos guys got hung up on the fact that you had bought a different brand from those your friend smokes. On top of that, your pal has no alibi. I’m sorry, Ellen, but at the moment he’s their main suspect.

‘By the way, I’ve just had a visitor. She’s called Rakel and works for POT. She popped up to see how I was, she said. She sat here for a while, although we didn’t say much. Then she left. I don’t think it went very well.

‘Helge says hello.’

54

Jens Bjelkes Gate. 14 March 2000.

‘HI, THIS IS ELLEN AND HELGE’S ANSWERPHONE. PLEASE leave a message.’

‘It’s the coldest March in living memory. The thermometer reads minus eighteen and the windows in this block are from the turn of the century. The popular notion that you don’t freeze when you’re drunk is a total fallacy. Ali, my neighbour, knocked on the door this morning. It turns out I had a nasty fall down the stairs coming home yesterday and he helped me to bed.

‘It must have been lunchtime before I got to work because the canteen was full of people when I went to get my morning cup of coffee. I had the impression they were staring at me, but perhaps I was imagining it. I miss you terribly, Ellen.

Blood on Snow: A novel

Blood on Snow: A novel Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8)

Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8) Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery Bubble in the Bathtub

Bubble in the Bathtub Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb The Bat

The Bat Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe.

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe. Silent (but Deadly) Night

Silent (but Deadly) Night Who Cut the Cheese?

Who Cut the Cheese? Headhunters

Headhunters The Jealousy Man and Other Stories

The Jealousy Man and Other Stories Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle

Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle The Thirst

The Thirst The Son

The Son The Redeemer

The Redeemer The Kingdom

The Kingdom The Snowman

The Snowman The Redbreast

The Redbreast Phantom

Phantom Macbeth

Macbeth The Leopard

The Leopard Blood on Snow

Blood on Snow Midnight Sun

Midnight Sun The Redbreast (Harry Hole)

The Redbreast (Harry Hole) The Devil's Star

The Devil's Star Cockroaches

Cockroaches The Magical Fruit

The Magical Fruit The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel

The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder The Cockroaches

The Cockroaches Knife

Knife Phantom hh-9

Phantom hh-9 The Redbreast hh-3

The Redbreast hh-3 The Redeemer hh-6

The Redeemer hh-6 The Leopard hh-8

The Leopard hh-8 The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel

The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel The Great Gold Robbery

The Great Gold Robbery Police hh-10

Police hh-10 The End of the World. Maybe

The End of the World. Maybe The Thirst: Harry Hole 11

The Thirst: Harry Hole 11 Nemesis - Harry Hole 02

Nemesis - Harry Hole 02 The Devil's star hh-5

The Devil's star hh-5 Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Time-Travel Bath Bomb