The Thirst Read online

Page 35

‘Aune, perhaps you and I should go and sit outside for a while, so they can look in peace.’

‘In peace? This is my daughter, Wyller, and she wants—’

‘Do as he says, Dad. I’m OK.’

‘Oh. Sure?’

‘Quite sure.’ Aurora turned to the woman from the bank and the man from the Street Crime Unit. ‘It’s not him, move on.’

Ståle Aune stood up, possibly a little too fast, perhaps that’s why he felt giddy. Or perhaps because he hadn’t got any sleep last night. Or eaten anything today. And had been looking at a screen for three hours without a break.

‘You sit down on this sofa here, and I’ll see if I can get us some coffee,’ Wyller said.

Ståle Aune just nodded.

Wyller walked off, leaving Ståle sitting there, looking at his daughter on the other side of the glass wall. She was gesturing at them to move on, stop, rewind. He couldn’t remember the last time he had seen her this engaged in anything. Perhaps his initial response and anxiety had been an overreaction. Perhaps the worst was over, perhaps she had somehow managed to move on, while he and Ingrid had been blissfully unaware of what had happened.

And his young daughter had explained to him – the way a psychology lecturer would explain something to a new student – what an oath of confidentiality was. And that she had imposed one on Harry, and that Harry hadn’t broken it until he realised that to do so could save people’s lives – exactly the same way Ståle applied his own oath of confidentiality. And Aurora had survived, in spite of everything. Death. Ståle had been thinking about that recently. Not his own, but the fact that his daughter would also die one day. Why was that thought so unbearable? Maybe it would look different if he and Ingrid became grandparents, seeing as the human psyche is obviously as much a slave to biological imperatives as physical ones, and the impulse to pass on your own genes is presumably a precondition for the survival of the species. He had once asked Harry, long ago, if he didn’t want a child that was biologically his own, but Harry had had his answer ready. He didn’t have the happy gene, only the alcoholic one, and he didn’t think anyone deserved to inherit that. It’s possible that he had changed his mind, because the last few years had at least proved that Harry was capable of experiencing happiness. Ståle took his phone out. He was thinking about phoning Harry and telling him that. That he was a good person, a good friend, father and husband. OK, it sounded like an obituary, but Harry needed to hear it. That he had been wrong to believe that his compulsive attraction to hunting murderers was similar to his alcoholism. That it wasn’t an act of escape, that what he was driven by, far more than Harry Hole the individualist was prepared to admit to himself, was the herding instinct. The good herding instinct. With morals and responsibility towards everyone. Harry would probably just laugh, but that’s what Ståle wanted to tell his friend, if only he’d answer his damn phone.

Ståle saw Aurora’s back straighten up, her muscles tense. Was it …? But then she relaxed again and gestured with her hand that they should go on.

Ståle held the phone to his ear again. Answer, damn it!

‘Successful at my career, sports and family life? Yes, maybe.’ Mikael Bellman looked round the table. ‘But first and foremost I’m just a simple guy from Manglerud.’

He had been worried that the practised clichés would sound hollow, but Isabelle had been right: it only took a little bit of feeling to deliver even the most embarrassing banality with conviction.

‘We’re glad you found the time for this little chat, Bellman.’ The Party Secretary raised his napkin to his lips to indicate that lunch was over, and nodded to the two other representatives. ‘The process is under way and, as I said, we’re extremely pleased that you’ve indicated that you’re inclined to respond positively in the event of an offer being made.’

Bellman nodded.

‘By “we”,’ Isabelle Skøyen interjected, ‘you mean the Prime Minister as well, don’t you?’

‘We wouldn’t have agreed to come here if it weren’t for the positive attitude of the Prime Minister’s office,’ the Party Secretary said.

At first they had invited Mikael to the Government Building for this conversation, but after consulting Isabelle, Mikael had countered by inviting them to neutral territory. Lunch, paid for by the Police Chief.

The Party Secretary looked at his watch. An Omega Seamaster, Bellman noted. Too heavy to be practical. And it made you a target for muggers in every Third World city. It stopped working if you left it off for longer than a day, so you had to wind and wind to reset the time, but if you forgot to tighten the screw afterwards and jumped in the pool, the clock was ruined and the repairs would cost more than four other high-quality watches. In short: he really needed to get that watch.

‘But, as I mentioned, there are other people under consideration. Minister of Justice is one of the weightier ministerial appointments, and I can’t deny that the path is slightly trickier for someone who hasn’t risen through the political ranks.’

Mikael made sure to get his timing spot on, and pushed back his chair and stood up at exactly the same time as the Party Secretary, and was first to hold out his hand and say ‘Let’s talk soon’. He was Chief of Police, damn it, and out of the two of them, it was him rather than this grey bureaucrat with the expensive watch who needed to get back to his responsible job fastest.

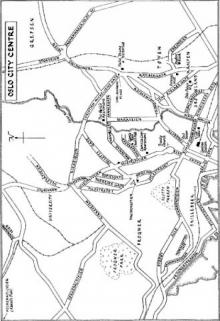

Once the representatives of the governing party had left, Mikael and Isabelle Skøyen sat down again. They had been given a private room in one of the new restaurants set among the apartment complexes at the far end of Sørenga. They had the Opera House and Ekebergsåsen behind them, and the new freshwater pool in front of them. The fjord was covered in choppy little waves, and the yachts hung crookedly out there like white commas. The latest weather forecasts predicted that the storm was going to hit Oslo before midnight.

‘That went OK, didn’t it?’ Mikael asked, pouring the last of the Voss mineral water into their glasses.

‘If it weren’t for the positive attitude from the Prime Minister’s office,’ Isabelle mimicked, and wrinkled her nose.

‘What’s wrong with that?’

‘That “if it weren’t for” is a modifier they haven’t used before. And the fact that they’re referring to the Prime Minister’s office instead of the Prime Minister herself tells me they’re distancing themselves.’

‘Why would they do that?’

‘You heard what I did. A lunch where they mostly asked you about the vampirist case and how quickly you think he can be caught.’

‘Come on, Isabelle, that’s what everyone in the city is talking about right now.’

‘They’re asking because that’s what everything depends on, Mikael.’

‘But—’

‘They don’t need you, your competence or ability to run a department, you do realise that, don’t you?’

‘Now you’re exaggerating, but OK, yes—’

‘They want your eyepatch, your hero status, popularity, success. Because that’s what you’ve got and what this government lacks right now. Take that away and you’re not worth anything to them. And, truth be told …’ She pushed her glass away and stood up. ‘… not to me either.’

Mikael smiled warily. ‘What?’

She took her short fur coat from the hat stand.

‘I can’t deal with losers, Mikael, you know that perfectly well. I went to the press and gave you the credit for saving the day by blowing the dust off Harry Hole. So far he’s arrested a naked ninety-year-old and got an innocent bartender murdered. That doesn’t just make you look like a loser, Mikael, it makes me look like one. I don’t like that, and that’s why I’m leaving you.’

Mikael Bellman laughed. ‘Have you got your period, or what?’

‘You used to know when that was due.’

‘OK,’ Mikael sighed. ‘Speak soon.’

‘I think you’re interpreting “leaving” a little too narrowly.’

‘Isabelle …’

‘Goodbye. I l

iked what you said about your successful family life. Focus on that.’

Mikael Bellman sat and watched the door close behind her.

He asked the waiter who looked in for the bill, and gazed out across the fjord again. It was said that the people who planned these apartments along the water’s edge hadn’t taken climate change and rising sea levels into account. He had actually thought about that when he and Ulla had their villa built, high up in Høyenhall: that they would be safe there, the sea couldn’t drown them, invisible assailants couldn’t sneak up on them, and no storm could blow the roof off. It would take more than that. He drank from his glass of water. Grimaced and looked at it. Voss. Why were people prepared to pay good money for something that tasted no better than what they could get from the tap? Not because they thought it tasted better, but because they thought other people thought it tasted better. So they ordered Voss when they were out at restaurants with their far-too-boring trophy wives and far-too-heavy Omega Seamaster watches. Was that why he sometimes found himself longing for the old days? For Manglerud, and being drunk at Olsen’s on a Saturday night, leaning over the bar and topping up his beer while Olsen looked the other way, dancing one last slow dance with Ulla as the first line of the Manglerud Stars and the Kawasaki 750 boys glared angrily at him, while he knew that he and Ulla would soon be leaving together, just the two of them, out into the night, walking down Plogveien towards the ice hall and Østensjøvannet, and there he would point out the stars and explain how they were going to get there.

Had they succeeded? Maybe, but it was like when he was a boy, when he was walking in the mountains with his father, when he was tired and thought they had finally reached the summit. Only to discover that beyond that summit lay one that was even higher.

Mikael Bellman closed his eyes.

It was just like that now. He was tired. Could he stop here? Lie down, feel the wind, the heather tickling him, sun-warmed rock against his skin. Say he was thinking of staying here. And he felt a peculiar urge to call Ulla and tell her just that. We’re staying here.

And in response he felt his phone vibrate in his jacket pocket. Of course, it had to be Ulla.

‘Yes?’

‘This is Katrine Bratt.’

‘Right.’

‘I just wanted to inform you that we’ve found out the alias Valentin Gjertsen has been hiding behind.’

‘What?’

‘He withdrew money at Oslo Central Station in August, and six minutes ago we managed to identify him from the recording made by the security camera. The card he used was issued to an Alexander Dreyer, born 1972.’

‘And?’

‘And this Alexander Dreyer died in a car accident in 2010.’

‘Address? Have we got an address?’

‘We have. Delta are on their way there now.’

‘Anything else?’

‘Not yet, but I presume you’d like to be kept informed as things develop?’

‘Yes. As things develop.’

They hung up.

‘Sorry.’ It was the waiter.

Bellman looked down at the bill. He tapped an amount that was far too high into the handheld card reader, and pressed Enter. Stood up and stormed out. Catching Gjertsen now would open all the doors.

His tiredness seemed to have blown away.

John D. Steffens turned the light on. The neon lights flickered for a few moments before the buzzing stabilised, casting a cold glow.

Oleg blinked and gasped. ‘Is that all blood?’ His voice echoed around the room.

Steffens smiled as the metal door slid closed behind them. ‘Welcome to the Bloodbath.’

Oleg shivered. The room was kept chilled, and the bluish light on the cracked white tiles only enhanced the feeling of being inside a fridge.

‘How … how much is there?’ Oleg asked as he followed Steffens between the rows of red blood bags, hanging four-deep from metal stands.

‘Enough for us to be able to cope for a few days if Oslo were attacked by Lakotas,’ Steffens said, climbing down the steps into the old pool.

‘Lakotas?’

‘You probably know them as Sioux,’ Steffens said, squeezing one of the bags, and Oleg saw the blood change colour, from dark to light. ‘It’s a myth that the Native Americans the white man met were especially bloodthirsty. Except for the Lakotas.’

‘Really?’ Oleg said. ‘What about the white man? Isn’t bloodthirstiness pretty evenly divided between types of people?’

‘I know that’s what you learn at school now,’ Steffens said. ‘No one’s better, no one’s worse. But believe me, the Lakotas were both better and worse, they were the best fighters. The Apaches used to say that if Cheyenne or Blackfoot warriors came, they would send their young boys and old men to fight them. But if the Lakotas came, they didn’t send anyone. They started to sing songs of death. And hoped for a quick end.’

‘Torture?’

‘When the Lakotas burned their prisoners of war, they did it gradually, with small pieces of charcoal.’ Steffens carried on to where the blood bags were hanging more densely and there was less light. ‘And when the prisoners couldn’t take any more, they were allowed a break with water and food, so that the torture could last a day or two. That food sometimes included chunks of their own flesh.’

‘Is that true?’

‘Well, as true as any written history. One Lakota warrior called Moon Behind Cloud was famous for drinking every drop of blood from all the enemies he killed. That’s clearly a historical exaggeration seeing as he killed a huge number of people and wouldn’t have survived the excessive drinking. Human blood is poisonous in high doses.’

‘Is it?’

‘You take in more iron than your body can get rid of. But he did drink someone’s blood, I know that much.’ Steffens stopped beside one blood bag. ‘In 1871 my great-great-grandfather was found drained of blood in Moon Behind Cloud’s Lakota camp in Utah, where he’d gone as a missionary. In my grandmother’s diary she wrote that my great-great-grandmother thanked the Lord after the massacre of Lakotas at Wounded Knee in 1890. Speaking of mothers …’

‘Yes?’

‘This blood is your mother’s. Well, it’s mine now.’

‘I thought she was receiving blood?’

‘Your mother has a very rare blood type, Oleg.’

‘Really? I thought she belonged to a fairly common blood group.’

‘Oh, blood’s about so much more than groups, Oleg. Luckily hers is group A, so I can give her ordinary blood from here.’ He held his hands out. ‘Ordinary blood that her body will absorb, and then turn into the golden drops which are Rakel Fauke’s blood. And speaking of Fauke, Oleg Fauke, I didn’t just bring you here to give you a break from sitting at her bedside. I was thinking of asking you if I could take a blood sample to see if you produce the same blood as her?’

‘Me?’ Oleg thought about it. ‘Yes, why not, if it could help someone.’

‘It would help me, believe me. Are you ready?’

‘Here? Now?’

Oleg met Dr Steffens’s gaze. Something made him hesitate, but he didn’t quite know what.

‘OK,’ Oleg said. ‘Help yourself.’

‘Great.’ Steffens put his hand in the right pocket of his white coat and took a step closer to Oleg. He frowned irritably when a cheerful tune rang out from his left pocket.

‘I didn’t think there was a signal down here,’ he muttered as he fished out his phone. Oleg saw the screen light up the doctor’s face, reflecting off his glasses. ‘Hello, it looks like it’s Police HQ.’ He put the phone to his ear. ‘Senior Consultant John Doyle Steffens.’

Oleg heard the buzz of the other voice.

‘No, Inspector Bratt, I haven’t seen Harry Hole today, and I’m fairly sure he isn’t here. This is hardly the only place where people have to switch their phones off, perhaps he’s sitting on a plane?’ Steffens looked at Oleg, who shrugged his shoulders. “We’ve found him”? Yes, Bratt, I’ll give him that message i

f he shows up. Who have you found, out of interest? … Thank you, I am aware of the oath of confidentiality, Bratt, but I thought it might be helpful to Hole if I didn’t have to speak in code. So that he understands what you mean … OK, I’ll just say “We’ve found him” to Hole when I see him. Have a good day, Bratt.’

Steffens put his phone back in his pocket. Saw that Oleg had rolled up his shirtsleeve. He took him by the arm and led him to the steps of the pool. ‘Thanks, but I just saw on my phone that it’s much later than I thought it was, and I’ve got a patient waiting. We’ll have to take your blood another time, Fauke.’

Sivert Falkeid, head of Delta, was sitting at the back of the rapid response unit’s van, barking out concise orders as they lurched along Trondheimsveien. There was an eight-man team in the vehicle. Well, seven men and one woman. And she wasn’t part of the response unit. No woman ever had been. The entry requirements to join Delta were in theory gender-neutral, but there hadn’t been a single woman among that year’s hundred or so applicants, and in the past there had only been five in total, the last of them in the previous millennium. And none of them had made it through the eye of the needle. But who knows, the woman sitting opposite him looked strong and determined, so perhaps she might stand a chance?

‘So we don’t know if this Dreyer is at home?’ Sivert Falkeid said.

‘Just so we’re clear, this is Valentin Gjertsen, the vampirist.’

‘I’m kidding, Bratt,’ Falkeid smiled. ‘So he hasn’t got a mobile phone we could use to pinpoint his location with?’

‘He may well have, but none that’s registered to Dreyer or Gjertsen. Is that a problem?’

Sivert Falkeid looked at her. They had downloaded plans from the Buildings Department of the City Council, and it looked promising. A 45-square-metre two-room apartment on the second floor, with no back door or cellar access directly from the flat. The plan was to send four men in through the front door, with two outside in case he jumped from the balcony.

‘No problem,’ he said.

‘Good,’ she said. ‘Go in silently?’

His smile widened. He liked her Bergen accent. ‘You’re thinking we should cut a neat hole in the glass on the balcony and wipe our shoes politely before going in?’

Blood on Snow: A novel

Blood on Snow: A novel Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8)

Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8) Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery Bubble in the Bathtub

Bubble in the Bathtub Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb The Bat

The Bat Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe.

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe. Silent (but Deadly) Night

Silent (but Deadly) Night Who Cut the Cheese?

Who Cut the Cheese? Headhunters

Headhunters The Jealousy Man and Other Stories

The Jealousy Man and Other Stories Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle

Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle The Thirst

The Thirst The Son

The Son The Redeemer

The Redeemer The Kingdom

The Kingdom The Snowman

The Snowman The Redbreast

The Redbreast Phantom

Phantom Macbeth

Macbeth The Leopard

The Leopard Blood on Snow

Blood on Snow Midnight Sun

Midnight Sun The Redbreast (Harry Hole)

The Redbreast (Harry Hole) The Devil's Star

The Devil's Star Cockroaches

Cockroaches The Magical Fruit

The Magical Fruit The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel

The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder The Cockroaches

The Cockroaches Knife

Knife Phantom hh-9

Phantom hh-9 The Redbreast hh-3

The Redbreast hh-3 The Redeemer hh-6

The Redeemer hh-6 The Leopard hh-8

The Leopard hh-8 The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel

The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel The Great Gold Robbery

The Great Gold Robbery Police hh-10

Police hh-10 The End of the World. Maybe

The End of the World. Maybe The Thirst: Harry Hole 11

The Thirst: Harry Hole 11 Nemesis - Harry Hole 02

Nemesis - Harry Hole 02 The Devil's star hh-5

The Devil's star hh-5 Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Time-Travel Bath Bomb