The Redbreast (Harry Hole) Read online

Page 4

‘What’s your name?’

The head moved and he saw the tips of trees and blue sky. He had been dreaming. Something in a poem. German bombers are overhead. Nordahl Grieg. The King fleeing to England. His pupils began to adjust to the light again and he remembered he had sat down on the grass in the Palace Gardens to rest. He must have fallen asleep. A little boy crouched beside him and a pair of brown eyes looked at him from under a black fringe.

‘My name’s Ali,’ the boy said.

A Pakistani boy? He had a strange, turned-up nose.

‘Ali means God,’ the boy said. ‘What does your name mean?’

‘My name’s Daniel,’ the old man said with a smile. ‘It’s a name from the Bible. It means “God is my judge”.’

The boy looked at him.

‘So, you’re Daniel?’

‘Yes,’ the man said.

The boy didn’t take his eyes off him and the old man felt disconcerted. Perhaps the young boy thought he was homeless as he was lying there fully clothed, using his woollen coat as a rug in the hot sun.

‘Where’s your mother?’ he asked, to avoid the boy’s probing stare.

‘Over there.’ The boy turned and pointed.

Two robust, dark-skinned women were sitting on the grass some distance away. Four children were frolicking around them, laughing.

‘Then I’m the judge of you, I am,’ the boy said.

‘What?’

‘Ali is God, isn’t he? And God is the judge of Daniel. And my name’s Ali and you’re —’

The old man had stuck out his hand and tweaked Ali’s nose. The boy squealed with delight. He saw the heads of the two women turn; one was getting to her feet so he let go.

‘Your mother, Ali,’ he said, motioning with his head in the direction of the approaching woman.

‘Mummy!’ the boy shouted. ‘Look, I’m the judge of that man.’

The woman shouted to the boy in Urdu. The old man smiled, but the woman shunned him and looked sternly at her son, who finally obeyed and padded over to her. When they turned, her gaze swept across and past him as if he were invisible. He wanted to explain to her that he was not a bum, to tell her he’d had a hand in shaping society. He had invested in it, in spades, given everything he had until there was no more to give, apart from giving way, giving in, giving up. But he was unable to do that, he was tired and simply wanted to go home. Rest, then he would see. It was time some others paid.

He didn’t hear the little boy shouting after him as he was leaving.

6

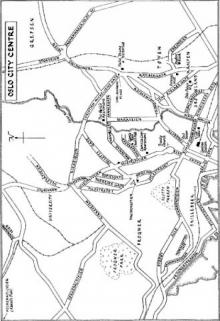

Police HQ, Grønland. 9 October 1999.

ELLEN GJELTEN LOOKED UP AT THE MAN WHO BURST through the door.

‘Good morning, Harry.’

‘Fuck!’

Harry kicked the waste-paper basket beside his desk and it smashed into the wall next to Ellen’s chair and rolled across the linoleum floor, spreading its contents everywhere: discarded attempts at reports (the Ekeberg killing); an empty pack of twenty cigarettes (Camel, tax free sticker); a green Go’morn yoghurt pot; Dagsavisen; a used cinema ticket (Filmteateret: Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas); a used pools coupon; a music magazine (MOJO, no. 69, February 1999, with a picture of Queen on the cover); a bottle of Coke (plastic, half-litre); and a yellow Post-it with a phone number he had considered ringing for a while.

Ellen looked up from her PC and studied the contents of the bin on the floor.

‘Are you chucking the MOJO out, Harry?’ she asked.

‘Fuck!’ Harry repeated. He wrestled off his tight suit jacket and threw it across the twenty metre square office he and Ellen Gjelten shared. The jacket hit the coat stand, but slid down to the floor.

‘What’s up?’ Ellen asked, reaching out a hand to stop the swaying coat stand from falling.

‘I found this in my pigeon-hole.’

Harry waved a document in the air.

‘Looks like a court sentence.’

‘Yep.’

‘Dennis Kebab case?’

‘Right.’

‘And?’

‘They gave Sverre Olsen the full whack. Three and a half years.’

‘Jesus. You ought to be in a stupendous mood.’

‘I was, for about a minute. Until I read this.’

Harry held up a fax.

‘Well?’

‘When Krohn got his copy of the sentence this morning, he responded by sending us a warning that he was going to pursue a claim of procedural error.’

Ellen made a face as if she had something nasty in her mouth.

‘Ugh.’

‘He wants the whole sentence quashed. You won’t fucking believe it, but that slippery Krohn guy has screwed us on the oath.’ Harry stood in front of the window. ‘The associate judges only have to take the oath the first time they act as judges, but it must take place in the courtroom before the case begins. Krohn noticed that one associate judge was new. And that she didn’t take her oath in the courtroom.’

‘It’s called affirmation.’

‘Right. Now it turns out that according to the certificate of sentence the judge had attended to the affirmation of the associate judge in his office, just before the case started. He blames lack of time and new rules.’

Harry crumpled up the fax and threw it in a wide arc, missing Ellen’s waste-paper basket by half a metre.

‘And the result?’ Ellen asked, kicking the fax to Harry’s half of the office.

‘The conviction will be deemed invalid and Sverre Olsen will be a free man for at least eighteen months until the case comes up again. And the rule of thumb is that the sentence will be a great deal milder because of the strain which the waiting period inflicts on the accused blah, blah, blah. With eight months already served in custody, it’s more than bloody likely that Sverre Olsen is already a free man.’

Harry wasn’t speaking to Ellen; she knew all the ins and outs of the case. He was speaking to his own reflection in the window, articulating the words to hear if they made any sense. He drew both hands across a sweaty skull, where until recently close-cropped blond hair had bristled. There was a simple reason for him having had the rest shaved off: last week he had been recognised again. A young guy, in a black woollen hat, Nikes and such large baggy trousers that the crotch hung between his knees, had come over to him while his pals sniggered in the background and asked if Harry was ‘that Bruce Willis type guy in Australia’. It was three – three! – years ago since his face had decorated the front pages of newspapers and he had made a fool of himself on TV shows talking about the serial killer he had shot in Sydney. Harry had immediately gone and shaved off his hair. Ellen had suggested a beard.

‘The worst thing is that I could swear that lawyer bastard had a draft appeal ready before the sentence was passed. He could have said something and the affirmation could have been taken there and then, but he sat there, rubbing his hands and waiting.’

Ellen shrugged her shoulders.

‘That sort of thing happens. Good work by the defence counsel. Something has to be sacrificed on the altar of law and order. Pull yourself together, Harry.’

She said it with a mixture of sarcasm and sober statement of fact.

Harry rested his forehead against the cooling glass. Another one of those unexpectedly warm October days. He wondered where Ellen, the fresh, young policewoman with the pale, doll-like, sweet face, the little mouth and eyes as round as a ball, had developed such a tough exterior. She was a girl from a middle-class home, in her own words, an only child and spoiled rotten, who had even gone to a girl’s boarding school in Switzerland. Who knows? Perhaps that was a tough enough upbringing.

Harry laid back his head and exhaled. Then he undid one of his shirt buttons.

‘More, more,’ Ellen whispered as she clapped encouragement.

‘In neo-Nazi circles they call him Batman.’

‘Got it. Baseball bat.’

‘Not the Nazi – the lawyer.’

‘Right. Interesting. Does that mean he’s good-looking, rich,

barking mad and has a six-pack and a cool car?’

Harry laughed. ‘You should have your own TV show, Ellen. It’s because Batman always wins. Besides, he’s married.’

‘Is that the only minus?’

‘That . . . and him making monkeys of us every time,’ Harry said, pouring himself a cup of the home-blended coffee Ellen had brought with her when she moved into the office two years ago. The snag was that Harry’s palate could no longer tolerate the usual slop.

‘Supreme Court judge?’ she asked.

‘Before he’s forty.’

‘Thousand kroner he isn’t.’

‘Done.’

They laughed and toasted with their cardboard cups.

‘Can I have that MOJO magazine then?’ she asked.

‘There are pictures of Freddie Mercury’s ten worst centrefold poses. Bare chest, arms akimbo and buck teeth sticking out. The full whammy. There you are.’

‘I like Freddie Mercury, I do. Liked.’

‘I didn’t say I didn’t like him.’

The blue, punctured office chair, which had long been set at the lowest notch, screamed in protest as Harry leaned back, lost in thought. He picked up a yellow Post-it with Ellen’s writing on from the telephone in front of him.

‘What’s this?’

‘You can read, can’t you? Møller wants you.’

Harry trotted down the corridor, imagining as he went the pursed mouth and the two deep furrows the boss would get when he heard that Sverre Olsen had walked yet again.

By the photocopier a young, rosy-cheeked girl instantly raised her eyes and smiled as Harry passed. He didn’t manage a return smile. Presumably one of the office girls. Her perfume was sweet and heavy, and simply irritated him. He looked at the second hand on his watch.

So perfume had started irritating him now. What had got into him? Ellen had said he lacked natural buoyancy, or whatever it was that meant most people could struggle to the surface again. After his return from Bangkok he had been down for so long that he had considered giving up ever returning to the surface. Everything had been cold and dark, and all his impressions were somehow dulled. As if he were deeply immersed in water. It had been so wonderfully quiet. When people talked to him the words had been like bubbles of air coming out of their mouths, hurrying upwards and away. So that was what it was like to drown, he had thought, and waited. But nothing happened. It was only a vacuum. That was fine, though. He had survived.

Thanks to Ellen.

She had stepped in for him in those first weeks after his return when he’d had to throw in the towel and go home. And she had made sure that he didn’t go to bars, ordered him to breathe out when he was late for work, after which she declared him fit or unfit accordingly. Had sent him home a couple of times and then kept quiet about it. It had taken time, but Harry had nothing particular to do. And Ellen had nodded with satisfaction on the first Friday they could confirm that he had turned up sober for work on five consecutive days.

In the end he had asked her straight out. Why, with police college and a law degree behind her and her whole life in front of her, had she voluntarily put this millstone around her neck? Didn’t she realise that it wouldn’t do her career any good? Did she have a problem finding normal, successful friends?

She had looked at him with a serious expression and answered that she only did it to soak up his experience. He was the best detective they had in Crime Squad. Rubbish, of course, but he had nonetheless felt flattered that she would bother to say so. Besides, Ellen was such an enthusiastic, ambitious detective that it was impossible not to be infected. For the last six months Harry had even begun to do good work again. Some of it even excellent. Such as on the Sverre Olsen case.

Ahead of him was Møller’s door. Harry nodded in passing to a uniformed officer who pretended not to see him.

If he had been a contestant on Swedish TV’s The Robinson Expedition, Harry thought, it would have taken them no more than a day to notice his bad karma and send him home. Send him home? My God, he was beginning to think in the same terminology as the shit TV3 programmes. That’s what happened when you spent five hours every night in front of the TV. The idea was that if he was locked up in front of the goggle box in Sofies gate, at least he wouldn’t be sitting in Schrøder’s café.

He knocked twice immediately beneath the sign on the door: Bjarne Møller, PAS.

‘Come in!’

Harry looked at his watch. Seventy-five seconds.

7

Møller’s Office. 9 October 1999.

INSPECTOR BJARNE MØLLER WAS LYING RATHER THAN sitting in the chair, and a pair of long limbs stuck out between the desk legs. He had his hands folded behind his head – a beautiful specimen of what early race researchers called ‘long skulls’ – and a telephone gripped between ear and shoulder. His hair was cut in a kind of close crop, which Hole had recently compared with Kevin Costner’s hairstyle in The Bodyguard. Møller hadn’t seen The Bodyguard. He hadn’t been to the cinema in fifteen years as fate had furnished him with an oversized sense of responsibility, too few hours, two children and a wife who only partly understood him.

‘Let’s go for that then,’ Møller said, putting down the phone and looking at Harry across a desk weighed down with documents, overflowing ashtrays and paper cups. On the desktop a photograph of two boys dressed as Red Indians marked a kind of logical centre amid the chaos.

‘There you are, Harry.’

‘Here I am, boss.’

‘I’ve been to a meeting at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in connection with the summit in November here in Oslo. The US President is coming . . . well, you read papers, don’t you. Coffee, Harry?’

Møller had stood up and a couple of seven-league strides had already taken him to a filing cabinet on which, balanced atop a pile of papers, a coffee machine was coughing up a viscous substance.

‘Thanks boss, but I —’

It was too late and Harry took the steaming cup.

‘I’m especially looking forward to a visit from the Secret Service, with whom I’m sure we will have a cordial relationship as we get to know each other better.’

Møller had never quite learned to handle irony. That was just one of the things Harry appreciated about his boss.

Møller drew in his knees until they supported the bottom of the table. Harry leaned back to get the crumpled pack of Camels from his trouser pocket and raised an enquiring eyebrow at Møller, who quickly took the hint and pushed the brimming ashtray towards him.

‘I’ll be responsible for security along the roads to and from Gardemoen. As well as the President, there will be Barak —’

‘Barak?’

‘Ehud Barak. Prime Minister of Israel.’

‘Jeez, so there’s another fantastic Oslo agreement on the way, then?’ Møller stared despondently at the blue column of smoke rising to the ceiling.

‘Don’t tell me you haven’t heard about it, Harry. Or I’ll be even more worried about you than I already am. It was on all the front pages last week.’

Harry shrugged.

‘Unreliable paper boy. Inflicting serious gaps in my general knowledge. A grave handicap to my social life.’ He took another cautious sip of coffee, but then gave up and pushed it away. ‘And my love life.’

‘Really?’ Møller eyed Harry with an expression suggesting he didn’t know whether to relish or dread what was coming next.

‘Of course. Who would find a man in his mid-thirties, who knows all the details about the lives of the people on The Robinson Expedition but can hardly name any head of state, or the Israeli President, sexy?’

‘Prime Minister.’

‘There you are. Now you know what I mean.’

Møller stifled a laugh. He had a tendency to laugh too easily. And a soft spot for the somewhat anguished officer with big ears that stuck out from the close-cropped cranium like two colourful butterfly wings. Even though Harry had caused Møller more trouble than was good for him. As a newly promot

ed PAS he had learned that the first commandment for a civil servant with career plans was to guard your back. When Møller cleared his throat to put the worrying questions he had made up his mind to ask, and dreaded asking, he first of all knitted his eyebrows to show Harry that his concern was of a professional and not an amicable nature.

‘I hear you’re still spending your time sitting in Schrøder’s, Harry.’

‘Less than ever, boss. There’s so much good stuff on TV.’

‘But you’re still sitting and drinking?’

‘They don’t like you to stand.’

‘Cut it out. Are you drinking again?’

‘Minimally.’

‘How minimally?’

‘They’ll throw me out if I drink any less.’

This time Møller couldn’t hold back his laughter. ‘I need three liaison officers to secure the road,’ he said. ‘Each will have ten men at their disposal from various police districts in Akershus, plus a couple of cadets from the final year at police college. I thought Tom Waaler . . .’

Waaler. Racist bastard and directly in line for the soon-to-be-announced inspector’s job. Harry had heard enough about Waaler’s professional activities to know that they confirmed all the prejudices the public might have about the police. Apart from one: unfortunately Waaler was not stupid. His successes as a detective were so impressive that even Harry had to concede he deserved the inevitable promotion.

‘And Weber . . .’

‘The old sourpuss?’

‘. . . and you, Harry.’

‘Say that again?’

‘You heard me.’

Harry pulled a face.

‘Have you any objections?’ Møller asked.

‘Of course I have.’

‘Why? This is an honourable mission, Harry. A feather in your cap.’

‘Is it?’ Harry stabbed out his cigarette furiously in the ashtray. ‘Or is it the next stage in the rehabilitation process?’

‘What do you mean?’ Bjarne Møller looked wounded.

‘I know that you defied good advice and had a run-in with a few people when you took me back into the fold after Bangkok. And I’m eternally grateful to you for that. But what is this? Liaison Officer? Sounds like an attempt to prove to the doubters that you were right, and they were wrong. That Hole is on his way up, that he can be given responsibility and all that.’

Blood on Snow: A novel

Blood on Snow: A novel Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8)

Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8) Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery Bubble in the Bathtub

Bubble in the Bathtub Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb The Bat

The Bat Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe.

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe. Silent (but Deadly) Night

Silent (but Deadly) Night Who Cut the Cheese?

Who Cut the Cheese? Headhunters

Headhunters The Jealousy Man and Other Stories

The Jealousy Man and Other Stories Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle

Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle The Thirst

The Thirst The Son

The Son The Redeemer

The Redeemer The Kingdom

The Kingdom The Snowman

The Snowman The Redbreast

The Redbreast Phantom

Phantom Macbeth

Macbeth The Leopard

The Leopard Blood on Snow

Blood on Snow Midnight Sun

Midnight Sun The Redbreast (Harry Hole)

The Redbreast (Harry Hole) The Devil's Star

The Devil's Star Cockroaches

Cockroaches The Magical Fruit

The Magical Fruit The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel

The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder The Cockroaches

The Cockroaches Knife

Knife Phantom hh-9

Phantom hh-9 The Redbreast hh-3

The Redbreast hh-3 The Redeemer hh-6

The Redeemer hh-6 The Leopard hh-8

The Leopard hh-8 The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel

The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel The Great Gold Robbery

The Great Gold Robbery Police hh-10

Police hh-10 The End of the World. Maybe

The End of the World. Maybe The Thirst: Harry Hole 11

The Thirst: Harry Hole 11 Nemesis - Harry Hole 02

Nemesis - Harry Hole 02 The Devil's star hh-5

The Devil's star hh-5 Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Time-Travel Bath Bomb