Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8) Read online

Page 40

Harry looked around the bar.

‘The lock on the back door was picked,’ the officer behind him said.

Harry nodded. He had seen the scratch marks around the lock.

Lock picking. Police handiwork. That was why the alarm hadn’t gone off.

Harry hadn’t seen any signs of resistance. No objects had been knocked over, nothing on the floor, no chairs or tables kicked out of a position it would be natural to leave them in overnight. The owner was being questioned. Harry had said he didn’t need to meet him. He hadn’t said he didn’t want to meet him. He hadn’t given any reason. Such as not wanting to risk being recognised.

Harry sat on a bar stool, reconstructing how he had sat there that night with an untouched glass of Jim Beam in front of him. The Russian had attacked from behind; he had tried to press the blade of the Siberian knife into his carotid artery. Harry’s titanium prosthesis had been in the way. The owner had stood behind the bar, paralysed with fear, as Harry had scrabbled for the corkscrew. The blood that had discoloured the floor beneath them, as if a full bottle of red wine had been knocked over.

‘Nothing in the way of clues so far,’ Bjørn said.

Harry nodded again. Of course not. Berntsen had had the place to himself, he was able to take his time. Clear up after him before he wet her, doused her . . . The word came to him without his wanting it to. Marinated her.

Then he had flicked the lighter.

Gram Parsons’ ‘She’ sounded and Bjørn lifted his phone to his ear.

‘Yes? . . . A match? Hang on . . .’

He took out a pencil and his ever-present Moleskine notebook. Harry suspected Bjørn liked the patina of the cover so much he erased the notes when the book was full and used it again.

‘No record, no, but he’s worked on murder investigations . . . Yes, I’m afraid we had a suspicion . . . And his name is?’

Bjørn had put his notebook down on the bar counter, ready to write. But the pencil tip stopped. ‘What did you say the father’s name was?’

Harry could hear from his colleague’s voice that something was wrong. Terribly wrong.

As Ståle Aune tore open the classroom door the following thoughts whirled through his head: he had been a bad father; he wasn’t sure if Aurora’s class had their own room; and if they did, if it was still this room.

It was two years since he had been here, during a school open day when all the classes had exhibited drawings, matchstick models, clay figures and other nonsense that had left him unimpressed. A better father would have been impressed of course.

The voices went quiet, and the class turned in his direction.

And in the silence he scoured the young, soft-skinned faces. The unscarred, undefiled faces that had not lived as long as they would, faces that were yet to be formed, yet to assume character and over the years stiffen into the mask which would become who they were inside. Which he had become. His girl.

His sweeping gaze found faces he had seen in class photos, at birthday parties, all too few handball games, last days of term. Some he could identify by name, most he couldn’t. Continued searching for the one face, as her name was formed, grew like a sob in his throat: Aurora. Aurora. Aurora.

Bjørn slipped the phone into his pocket. Stood by the counter with his back to Harry, motionless. Slowly shaking his head. Then he turned. His face looked as if it had been bled. Pale, bloodless.

‘It’s someone you know well,’ Harry said.

Bjørn nodded slowly, like a sleepwalker. Swallowed. ‘It just can’t be possible . . .’

‘Aurora.’

The wall of faces gawped up at Ståle Aune. Her name had crossed his lips like a sob. Like a prayer.

‘Aurora,’ he repeated.

At the margins of his field of vision he saw the teacher move towards him.

‘What isn’t possible?’ Harry asked.

‘His daughter,’ Bjørn said. ‘It . . . just can’t be possible.’

Ståle’s eyes were swimming with tears. He felt a hand on his shoulder. Then a figure rose, came towards him, the contours blurred like in a fairground mirror. Yet he thought the figure resembled her. Resembled Aurora. As a psychologist he of course knew that this was the brain’s escape, our way of tackling the intolerable, of lying. Of seeing what we want to see. Nevertheless he whispered her name.

‘Aurora.’

And he could even swear the voice was hers.

‘Is something the matter . . .?’

He also heard the last word at the end of the sentence, but wasn’t sure if it was her or his brain that had added it.

‘. . . Dad?’

‘Why isn’t it possible?’

‘Because . . .’ Bjørn said, staring at Harry as though he wasn’t there.

‘Yes?’

‘Because she’s already dead.’

41

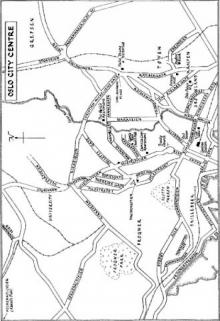

IT WAS A quiet morning in Vestre Cemetery. All that could be heard was the distant hum of traffic in Sørkedalsveien and the clatter of the trams conveying people to the city centre.

‘Roar Midtstuen, yes,’ Harry said, striding between the gravestones. ‘How many years has he actually been with you?’

‘No one knows,’ Bjørn said, struggling to keep up. ‘Since the dawn of time.’

‘And his daughter died in a car accident?’

‘Last summer. It’s sick. It just can’t be right. They’ve only got the first part of the DNA code. There’s still a ten, fifteen per cent chance it’s someone else’s DNA, perhaps someone—’ He almost walked into Harry, who had come to a sudden halt.

‘Well,’ Harry said, sinking to his knees and sticking his fingers into the earth by the gravestone bearing Fia Midtstuen’s name, ‘that chance just plummeted to zero.’ He raised his hand and sprinkled freshly dug soil between his fingers. ‘He dug up the body, transported it to Come As You Are. And set fire to it.’

‘F . . .’

Harry heard the tears in his colleague’s voice. Avoided looking at him. Left him in peace. Waited. Closed his eyes, listened. A bird sang a – to human ears – meaningless song. The carefree, whistling wind nudged the clouds along. A metro train rattled westwards. Time went, but did it have anywhere to go any more? Harry opened his eyes again. Coughed.

‘We’d better ask them to dig up the coffin and have this confirmed before we contact the father.’

‘I’ll do that.’

‘Bjørn,’ Harry said, ‘this is better. This wasn’t a young girl burned alive. OK?’

‘Sorry, I’m just exhausted. And Roar was in a bad enough state before, so I . . .’ He threw up his arms in desperation.

‘That’s fine,’ Harry said, getting up.

‘Where are you going?’

Harry looked to the north, to the road and the metro. The clouds were drifting towards him. A northerly. And there it was again. The sensation that he knew something he didn’t know yet, something down there in the murky depths inside him, but it would not float to the surface.

‘I have to take care of something.’

‘Where?’

‘Just something I’ve put off for too long.’

‘Right. By the way, there was something I was wondering about.’

Harry glanced at his watch and nodded.

‘When you spoke to Bellman yesterday what did he think could have happened to the bullet?’

‘He had no idea.’

‘What about you? You usually have at least one hypothesis.’

‘Mm. I’ve got to be off.’

‘Harry?’

‘Yes?’

‘Don’t . . .’ Bjørn gave a sheepish smile. ‘Don’t do anything stupid.’

Katrine Bratt leaned back in her chair and looked at the screen. Bjørn Holm had just rung to say they had found the father, a Midtstuen who had investigated the murder of Kalsnes, but the reason they hadn’t found him among the police officers with young daughters was that his daughter was already dead. And as that meant Katrine was temporarily unemployed she had

looked at her search history from the day before. They hadn’t had any hits for Mikael Bellman and René Kalsnes. When she had looked for a list of the people most frequently connected with Mikael Bellman, three names stood out. First was Ulla Bellman. Then came Truls Berntsen. And in third place, Isabelle Skøyen. It was no surprise that his wife came first, nor was it strange that the Councillor for Social Affairs, his superior, should come third.

But she was taken aback by Truls Berntsen.

For the simple reason that there was an internal note directed from Fraud Squad to the Police Chief, written right there in Police HQ. There was a cash sum that Truls Berntsen refused to account for, and they had asked for permission to start an investigation into possible corruption.

She couldn’t find an answer, so she supposed that Bellman must have given a verbal response.

What she found strange was that the Chief of Police and an apparently corrupt policeman had rung and exchanged texts so often, used credit cards at the same places and at the same times, travelled at the same time by plane and train, checked into the same hotel on the same date and had been in the same firing range. When Harry had told her to run a thorough check on Bellman, she discovered that Bellman had been watching gay porn online. Could Truls Berntsen be his lover?

Katrine sat looking at the screen.

So what? It didn’t have to mean anything.

She knew Harry had met Bellman the previous night, in Valle Hovin. And confronted him with the discovery of his bullet. And before leaving Harry had mumbled something about a feeling he knew who had switched the bullet in the Evidence Room. To her enquiry, Harry had only answered ‘The Shadow’.

Katrine widened her search to include more of the past.

She read through the results.

Bellman and Berntsen were inseparable throughout their careers. Which had clearly started at Stovner Police Station after they had left Police College.

She got up a list of other employees during that period.

Her eyes ran down the screen. Stopped at one name. Dialled a number starting with 55.

‘And high time too, frøken Bratt,’ the voice sang, and she felt so liberated to hear genuine Bergen dialect again. ‘You were supposed to have been here for a physical examination some time ago!’

‘Hans—’

‘Dr Hans, thank you very much. Please be so kind as to remove your top, Bratt.’

‘Pack it in,’ she warned him, with a smile on her lips.

‘May I ask you not to confuse medical expertise with unwanted sexual attentions in the workplace, Bratt?’

‘Someone told me you were back on the beat.’

‘Yep. And where are you at this minute?’

‘In Oslo. By the way, I can see from a list here that you worked at Stovner Police Station at the same time as Mikael Bellman and Truls Berntsen.’

‘That was straight after Police College, and only because of a woman, Bratt. The nightmare with the knockers – have I told you about her?’

‘Probably.’

‘But when it was all over with her, it was over with Oslo as well.’ He burst into song. ‘Vestland, Vestland über alles—’

‘Hans! When you worked with—’

‘No one worked with those two boys, Katrine. You either worked for them or you worked against them.’

‘Truls Berntsen has been suspended.’

‘And high time too. He’s beaten someone up again, I assume?’

‘Beaten up? Did he beat up prisoners?’

‘Worse than that. He beat up police officers.’

Katrine felt the hairs on her arms stand on end. ‘Oh? Who did he beat up?’

‘Everyone who tried it on with Bellman’s wife. Beavis Berntsen was head over heels in love with them both.’

‘What did he use?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘When he beat them up.’

‘How should I know? Something hard, I suppose. At least it looked like that when that young Nordlander was stupid enough to dance too close to fru Bellman at the Christmas dinner.’

‘Which Nordlander?’

‘His name was . . . let me see . . . something with R. Yes, Runar. It was Runar. Runar . . . let me see now . . . Runar . . .’

Come on, Katrine thought, as her fingers automatically scampered across the keyboard.

‘Sorry, Katrine, it’s a long time ago. Perhaps if you take off your top?’

‘Tempting,’ Katrine said. ‘But I’ve found it without your help. There was only one Runar at Stovner at that time. Bye, Hans—’

‘Wait! A little mammogram doesn’t have to—’

‘Have to run, sicko.’

She rang off. Pressed Enter. Let the search engine work while she stared at the surname. There was something familiar about it. Where had she heard it? She closed her eyes, mumbling the name to herself. It was so unusual it couldn’t be chance. She opened her eyes. The result was in. There was a lot. Enough. Medical records. Admission to hospital for drug addiction. The correspondence between the head of a detox clinic in Oslo and the Police Chief. Pure, innocent, blue eyes looking at her. She suddenly knew where she had seen them before.

Harry let himself into the house, and strode over to the CD shelf without removing his shoes. Stuck his fingers between Waits’s Bad As Me and A Pagan Place which he had placed first in the line of the Waterboys CDs, though not without some agonising, as strictly speaking it was a remastered version from 2002. It was the safest place in the house. Neither Rakel nor Oleg had ever voluntarily selected a CD featuring Tom Waits or Mike Scott.

He coaxed out the key. Brass, small and hollow, weighing almost nothing. And yet it felt so heavy that his hand seemed to be drawn towards the floor as he went over to the corner cupboard. He inserted it in the keyhole and turned. Waited. Knowing there was no way back after he had opened it. The promise would be broken.

He had to use his strength to pull open the swollen cupboard door. He knew it was only old wood being released by the frame but it sounded as though a deep sigh came from inside the darkness. As though it realised it was free at last. Free to inflict hell on earth.

It smelt of metal and oil.

He inhaled. Felt as if he was sticking his hand into a den of snakes. His fingers groped before finding the cold, scaly skin of steel. He grabbed the reptile’s head and lifted it out.

It was an ugly weapon. Fascinatingly ugly. Soviet Russian engineering at its most brutally effective, it could take as much of a beating as a Kalashnikov.

Harry weighed the gun in his hand.

He knew it was heavy, and yet it felt light. Light now that the decision had been taken. He breathed out. The demon was free.

‘Hi,’ Ståle said, closing the Boiler Room door behind him. ‘Are you alone?’

‘Yeah,’ Bjørn said from his chair, staring at the phone.

Ståle sat down on a chair. ‘Where . . .?’

‘Harry had to sort something out. Katrine was gone when I arrived.’

‘You look as if you’ve had a tough day.’

Bjørn smiled wanly. ‘You, too, Dr Aune.’

Ståle ran a hand across his pate. ‘Well, I’ve just entered a classroom, embraced my daughter and sobbed with the whole class watching. Aurora claims it was an experience that will mark her for life. I tried to explain to her that fortunately most children are born with enough strength to bear the burden that is their parents’ love and that from a Darwinian point of view she should therefore be able to survive this as well. All because she had a sleepover with Emilie and there are two Emilies in the class. I rang the mother of the wrong Emilie.’

‘Did you get the message that we’ve postponed the meeting for today? A body has been found. Of a girl.’

‘Yes, I know. It was grim by all accounts.’

Bjørn nodded slowly. Pointed to the phone. ‘I have to ring the father now.’

‘You’re dreading it of course.’

‘Of course.’

‘You

’re wondering why the father has to be punished in this way? Why he has to lose her twice? Why once isn’t enough?’

‘That sort of thing.’

‘The answer is because the murderer sees himself as the divine avenger, Bjørn.’

‘Oh yeah?’ Bjørn said, sending the psychologist a vacant look.

‘Do you know your Bible? “God is jealous, and the Lord revengeth; the Lord revengeth, and is furious; the Lord will take vengeance on his adversaries, and he reserveth wrath for his enemies.” You get the gist anyway, don’t you?’

‘I’m a simple boy from Østre Toten who scraped through confirmation and—’

‘That’s why I’m here now.’ Ståle leaned forward in his chair. ‘The murderer is an avenger, and Harry’s right, he kills out of love, not out of hatred, profit or sadistic enjoyment. Someone has taken something from him that he loved, and now he’s taking from the victims what they loved most. It could be their lives. Or something they value more: their children.’

Bjørn nodded. ‘Roar Midtstuen would have happily given his life to save his daughter.’

‘So what we have to look for is someone who’s lost something they loved. An avenger out of love. Because that . . .’ Ståle Aune clenched his right hand. ‘. . . because that’s the only motive that’s strong enough here, Bjørn. Do you understand?’

Bjørn nodded. ‘I think so. But I reckon I’ll have to call Midtstuen now.’

‘I’ll leave you in peace then.’

Bjørn waited until Ståle had gone, then he dialled the number he had been looking at for so long it felt as if it had been stamped on his retina. He took deep breaths as he counted the rings. Wondering how many times he should let it ring before putting the receiver down. Then all of a sudden he heard his colleague’s voice.

Blood on Snow: A novel

Blood on Snow: A novel Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8)

Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8) Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery Bubble in the Bathtub

Bubble in the Bathtub Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb The Bat

The Bat Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe.

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe. Silent (but Deadly) Night

Silent (but Deadly) Night Who Cut the Cheese?

Who Cut the Cheese? Headhunters

Headhunters The Jealousy Man and Other Stories

The Jealousy Man and Other Stories Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle

Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle The Thirst

The Thirst The Son

The Son The Redeemer

The Redeemer The Kingdom

The Kingdom The Snowman

The Snowman The Redbreast

The Redbreast Phantom

Phantom Macbeth

Macbeth The Leopard

The Leopard Blood on Snow

Blood on Snow Midnight Sun

Midnight Sun The Redbreast (Harry Hole)

The Redbreast (Harry Hole) The Devil's Star

The Devil's Star Cockroaches

Cockroaches The Magical Fruit

The Magical Fruit The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel

The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder The Cockroaches

The Cockroaches Knife

Knife Phantom hh-9

Phantom hh-9 The Redbreast hh-3

The Redbreast hh-3 The Redeemer hh-6

The Redeemer hh-6 The Leopard hh-8

The Leopard hh-8 The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel

The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel The Great Gold Robbery

The Great Gold Robbery Police hh-10

Police hh-10 The End of the World. Maybe

The End of the World. Maybe The Thirst: Harry Hole 11

The Thirst: Harry Hole 11 Nemesis - Harry Hole 02

Nemesis - Harry Hole 02 The Devil's star hh-5

The Devil's star hh-5 Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Time-Travel Bath Bomb