Phantom hh-9 Read online

Page 7

‘I keep hearing about this violin stuff. What is it?’

‘New synthetic dope. It doesn’t hinder breathing as much as standard heroin, so even if it ruins lives there are fewer overdoses. Extremely addictive. Everyone who tries it wants more. But it’s so expensive not many can afford it.’

‘So they buy other dope instead?’

‘There’s a morphine bonanza.’

‘One step forward, two steps back.’

Beate shook her head. ‘It’s the war on heroin that’s important. And he’s won that one.’

‘Bellman?’

‘So you’ve heard?’

‘Hagen said he’s busted most of the heroin gangs.’

‘The Pakistani gangs. The Vietnamese. Dagbladet called him General Rommel after he smashed a major network of North Africans. The MC gang in Alnabru. They’re all banged up.’

‘The bikers? In my time biker boys sold speed and shot heroin like crazy.’

‘Los Lobos. Hell’s Angels wannabes. We reckon they were one of only two networks dealing in violin. But they were caught in a mass arrest with a subsequent raid in Alnabru. You should have seen the smirk on Bellman’s chops in the papers. He was there when they carried out the operation.’

‘Let’s do some good?’

Beate laughed. Another feature he liked about her: she was enough of a film buff to be on the ball when he quoted semi-good lines from semi-bad films. Harry offered her a cigarette, which she declined. He lit up.

‘Mm. How the hell did Bellman achieve what the Narc Unit wasn’t even close to achieving in all the years I was at HQ?

‘I know you don’t like him, but in fact he’s a good leader. They loved him at Kripos, and they’re pissed off with the Chief of Police for taking him to Police HQ.’

‘Mm.’ Harry inhaled. Felt it pacify his blood’s hunger. Nicotine. A polysyllabic word, like heroin, like violin. ‘So who’s left?’

‘That’s the snag with exterminating pests. You upset a food chain and you don’t know if all you’ve done is make way for something else. Something worse than what you removed…’

‘Any evidence of that?’

Beate shrugged.

‘All of a sudden we’re not getting any info off the streets. Our informers don’t know anything. Or they’re keeping shtum. There are just whispers about the man from Dubai. No one has seen him, no one knows his name, he’s a kind of invisible puppeteer. We can see violin is being sold, but we can’t trace it back to its source. The pushers we nab say they’ve bought off other sellers at the same level. It’s not normal for tracks to be covered so well. And that tells us this is a simple, very professional outfit controlling import and distribution.’

‘The man from Dubai. The mysterious mastermind. Haven’t we heard that story before? And then he turns out to be a run-of-the-mill crook.’

‘This is different, Harry. There were a number of drugs-related murders over the new year. A type of brutality we haven’t seen before. And no one says a word. Two Vietnamese dealers are found hanging upside down from a beam in the flat where they worked. Drowned. Each one had a plastic bag filled with water on his head.’

‘That’s not an Arab method, it’s Russian.’

‘Sorry?’

‘They hang them upside down, put a plastic bag over their heads and tie it loosely, around the neck. Then they begin to pour water down their heels. It follows the body down to the bag and fills it up. The method’s called the Man on the Moon.’

‘How do you know that?’

Harry shrugged. ‘There was a wealthy surgeon called Birayev. In the eighties he got his hands on one of the original astronaut suits from Apollo 11. Two million dollars on the black market. Anyone who tried to pull a fast one on Birayev or didn’t pay a debt was put in the suit. They filmed the face of the poor guy as they poured in the water. Afterwards the film was sent round to other debtors.’

Harry blew smoke towards the ceiling.

Beate sent him a lingering look and slowly shook her head. ‘What have you been doing in Hong Kong, Harry?’

‘You asked me that on the phone.’

‘And you didn’t answer.’

‘Exactly. Hagen said he could give me another case instead of this one. Mentioned something about an undercover guy who was killed.’

‘Yes,’ Beate said, sounding relieved that they were no longer talking about the Gusto case and Oleg.

‘What was that about?’

‘A young undercover Narc agent. He was washed ashore where the Opera House slopes into the water. Tourists, children, and so on. Big hullabaloo.’

‘Shot?’

‘Drowned.’

‘And how do you know it was murder?’

‘No external injuries; in fact, it looked as if he might have fallen into the sea by accident — his beat was the area around the Opera House. But then Bjorn Holm checked his lungs. Turned out it was fresh water. And Oslo fjord is salt water as you know. Looks like someone chucked him in the sea to make it look as if he had drowned there.’

‘Well,’ Harry said, ‘as a Narc agent he must have wandered up and down the river. That’s fresh water and it flows into the sea by the Opera House.’

Beate smiled. ‘Good to have you back, Harry. But Bjorn thought about that, and compared the bacterial flora, the content of microorganisms, and so on. The water in his lungs was too clean to have come from the Akerselva. It had been through water filters. My guess is he drowned in a bath. Or in a pool below the water-purification plant. Or…’

Harry threw the butt down on the path in front of him. ‘A plastic bag.’

‘Yes.’

‘The Man from Dubai. What do you know about him?’

‘What I’ve just told you, Harry.’

‘You didn’t tell me anything.’

‘Exactly.’

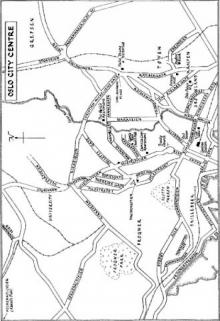

They stopped by Anker Bridge. Harry checked his watch.

‘Going somewhere?’ Beate asked.

‘Nope,’ Harry answered. ‘I did it to give you a pretext to say you’ve got to be off, without feeling you were dumping me.’

Beate smiled. She was quite attractive when she smiled, Harry thought. Strange that she wasn’t with someone. Or perhaps she was. One of the eight in his phone contacts list, and he didn’t even know that.

B for Beate.

H was for Halvorsen, Harry’s ex-colleague and the father of Beate’s child. Killed on active duty. But his number still hadn’t been deleted.

‘Have you contacted Rakel?’ Beate asked.

R. Harry wondered if her name had come up as a result of association with the word ‘dump’. He shook his head. Beate waited. But he had nothing to add.

They both started to speak at the same time.

‘I suppose you’ve-’

‘In fact, I have-’

She smiled. ‘-got to be off.’

‘Of course.’

He watched her walk up towards the road.

Then he sat on one of the benches and stared at the river, at the ducks paddling in a quiet backwater.

The two hoodies returned. Came over to him.

‘Are you five-o?’

American slang for police, stolen from a supposedly authentic TV series. It was Beate they had smelt, not him.

Harry shook his head.

‘After some…?’

‘Some peace,’ Harry completed. ‘Peace and quiet.’

He took a pair of Prada sunglasses from his inside pocket. He had been given them by a shopowner on Canton Road who was a bit behind with payments, but who considered himself fairly treated. They were a ladies’ model, but Harry didn’t care, he liked them.

‘By the way,’ he called after them, ‘got any violin?’

One snorted by way of response. ‘Town centre,’ the other said, pointing over his shoulder.

‘Where precisely?’

‘Look for Van Persie or Fabregas.’ Their laughter faded as they headed towards Bla, the jazz club.

Harry leaned back

and studied the ducks’ strangely efficient kick that allowed them to glide across the water like speed skaters on black ice.

Oleg was keeping his mouth shut. The way the guilty keep their mouths shut. That is their privilege and sole rational strategy. So where to go from here? How do you investigate something that is already solved, answer questions that have already found adequate answers? What did he think he could achieve? Defeat the truth by denying it? The way he, in his role as a Crime Squad detective, had seen relatives produce the pathetic refrain: ‘My son? Not a chance!’ He knew why he wanted to investigate crimes. Because it was the only thing he could do. The only thing he had to contribute. He was the housewife who insisted on cooking at her son’s wake, the musician who took his instrument to his friend’s funeral. The need to do something, as a distraction or a gesture of comfort.

One of the ducks glided towards him, hoping for a few crumbs of bread perhaps. Not because it was confident, but you never knew. It had calculated consumption of energy versus probability of reward. Hope. Black ice.

Harry sat up with a start. Took the keys from his jacket pocket. He had just remembered why he had bought the padlock that time. It hadn’t been for himself. It had been for the speed skater. For Oleg.

7

Officer Truls Berntsen had had a brief discussion with the duty inspector at the airport. Berntsen had said yes, he knew the airport was in the Romerike Police District, and he had nothing to do with the arrest, but as a Special Operations detective he had been keeping an eye on the arrested man for a while and had recently been warned by one of his sources that Tord Schultz had been caught with narcotics in his possession. He had held up his ID card showing he was a grade 3 police officer, employed in Oslo Police District by Special Operations and Orgkrim. The inspector had shrugged and without further ado taken him to one of the three remand cells.

After the cell door had slammed behind Truls he looked around to ensure the corridor and the other two cells were empty. Then he sat down on the toilet lid and looked at the slat bed and the man with his head buried in his hands.

‘Tord Schultz?’

The man raised his head. He had removed his jacket, and had it not been for the flashes on his shirt Berntsen would not have recognised him as the chief pilot of an aircraft. Captains should not look like this. Not petrified, pale, with pupils that were large and black with shock. On the other hand, it was how most people looked after they had been apprehended for the first time. It had taken Berntsen a little while to locate Tord Schultz in the airport. But the rest was easy. According to STRASAK, the official criminal register, Schultz did not have a record, had never had any dealings with the police and was — according to their unofficial register — not someone with known links to the drugs community.

‘Who are you?’

‘I’m here on behalf of the people you work for, Schultz, and I don’t mean the airline. Screw the rest. Alright?’

Schultz pointed to the ID card hanging from a string around Berntsen’s neck. ‘You’re a policeman. You’re trying to trick me.’

‘It would be good news if I was, Schultz. It would be a breach of procedures and a chance for your solicitor to have you acquitted. But we’ll manage this without solicitors. Alright?’

The airline captain continued to stare with dilated pupils absorbing all the light they could, the slightest glimpse of optimism. Truls Berntsen sighed. He could only hope that what he was going to say would sink in.

‘Do you know what a burner is?’ Berntsen asked, pausing only briefly for an answer. ‘It’s someone who destroys police cases. He makes sure that evidence becomes contaminated or goes missing, that mistakes are made in legal procedures, thus preventing a case from being brought to court, or that everyday blunders are made in the investigation, thus allowing the suspect to walk away free. Do you understand?’

Schultz blinked twice. And nodded slowly.

‘Great,’ Berntsen said. ‘The situation is that we are two men in free fall with the one parachute between us. I’ve jumped out of the plane to rescue you, for the moment you can spare me the gratitude, but you must trust me one hundred per cent, otherwise we’ll both hit the ground. Capisce?’

More blinking. Obviously not.

‘There was once a German policeman, a burner. He worked for a gang of Kosovar Albanians importing heroin via the Balkan route. The drugs were driven in lorries from the opium fields in Afghanistan to Turkey, transported onwards through ex-Yugoslavia to Amsterdam where the Albanians channelled it on to Scandinavia. Loads of borders to cross, loads of people to be paid. Among them, this burner. And one day a young Kosovar Albanian is caught with a petrol tank full of raw opium, the clumps weren’t wrapped up, just put straight into the petrol. He was held in custody, and the same day the Kosovar Albanians contacted their German burner. He went to the young man, explained that he was his burner and he could relax now, they would fix this. The burner said he would be back the next day and tell him what statement to make to the police. All he had to do was keep his mouth shut. But this guy who had been nabbed red-handed had never served time before. He had probably heard too many stories about bending over in the prison showers for the soap; at any rate he cracked like an egg in the microwave at the first interview and blew the whistle on the burner in the hope that he would receive favourable treatment from the judge. So. In order to get evidence against the burner the police put a hidden microphone in the cell. But the burner, the corrupt policeman, did not turn up as arranged. They found him six months later. Spread over a tulip field in bits. I’m a city boy myself, but I’ve heard bodies make good manure.’

Berntsen stopped and looked at the pilot while waiting for the usual question.

The pilot had sat up straight on the bed, recovered some colour in his face and at length cleared his throat. ‘Why… erm, the burner? He wasn’t the one who grassed.’

‘Because there is no justice, Schultz. There are only necessary solutions to practical problems. The burner who was going to destroy the evidence had become evidence himself. He had been rumbled, and if the police caught him he could lead the detectives to the Kosovar Albanians. Since he wasn’t one of their brothers, only a corrupt cop, it was logical to expedite him into the beyond. And they knew this was the murder of a policeman the police would not prioritise. Why should they? The burner had already received his punishment, and the police don’t set up an investigation where the only goal they will achieve is to inform the public about police corruption. Agreed?’

Schultz didn’t answer.

Berntsen leaned forward. The voice went down in volume and up in intensity. ‘I do not want to be found in a tulip field, Schultz. Our only way out of this is to trust each other. One parachute. Got that?’

The pilot cleared his throat. ‘What about the Kosovar Albanian? Did he have his sentence commuted?’

‘Hard to say. He was found hanging from the cell wall before the case came to court. Someone had smashed his head against a clothes hook.’

The captain’s face lost its colour again.

‘Breathe, Schultz,’ Truls Berntsen said. That was what he liked best about this job. The feeling that he was in charge for once.

Schultz leaned back and rested his head against the wall. Closed his eyes. ‘And if I decline your help outright and we pretend you’ve never been here?’

‘Won’t do. Your employer and mine don’t want you in the witness box.’

‘So, what you’re saying is I have no choice?’

Berntsen smiled. And uttered his favourite sentence: ‘Schultz, it’s a long time since you had any choice.’

Valle Hovin Stadium. A little oasis of concrete in the middle of a desert of green lawns, birch trees, gardens and flowerboxes on verandas. In the winter the track was used as a skating rink, in the summer as a concert venue, by and large for dinosaurs like the Rolling Stones, Prince and Bruce Springsteen. Rakel had even persuaded Harry to go along with her to see U2, although he had always been a club man and h

ated stadium concerts. Afterwards she had teased Harry that in his heart of hearts he was a closet music fundamentalist.

Most of the time, however, Valle Hovin was as now, deserted, run-down, like a disused factory which had manufactured a product that was no longer used. Harry’s best memories from here were seeing Oleg training on the ice. Sitting and watching him try his hardest. Fighting. Failing. Failing. Then succeeding. Not great achievements: a new PB, second place in a club championship for his age group. But more than enough to make Harry’s foolish heart swell to such an absurd size that he had to adopt an indifferent air so as not to embarrass both of them. ‘Not bad that, Oleg.’

Harry looked around. Not a soul in sight. Then he inserted the Ving key in the lock of the dressing-room door beneath the stands. Inside, everything was unchanged, except more worn. There was refuse on the floor; it was clearly a long time since anyone had been here. It was a place you could be alone. Harry walked between the lockers. Most were not locked. But then he found what he was looking for, the Abus padlock.

He pushed the tip of the key into the jagged aperture. It wouldn’t go in. Shit.

Harry turned. Let his eyes glide along the bulky iron cabinets. Stopped, went back one locker. That was another Abus padlock. And there was a circle etched into the green paint. An ‘O’.

The first objects Harry saw when he opened up were Oleg’s racing skates. The long, slim blades had a kind of red rash along the edge.

On the inside of the cabinet door, stuck to the ventilation grille, were two photographs. Two family photographs. One showed five faces. Two of the children and what he assumed were the parents were unfamiliar. But he recognised the third child. Because he had seen him in other photographs. Crime-scene photographs.

It was the good looks. Gusto Hanssen.

Harry wondered whether it was the good looks that did it, the immediate sensation that Gusto Hanssen did not belong in the photograph. Or, to be precise, that he didn’t belong to the family.

The same, strangely enough, could be said about the tall, blond man sitting behind the dark-haired woman and her son in the second photograph. It had been taken one autumn day several years ago. They had gone for a walk in Holmenkollen, waded through the orange-coloured foliage, and Rakel had placed her camera on a rock and pressed the self-timer button.

Blood on Snow: A novel

Blood on Snow: A novel Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8)

Police: A Harry Hole thriller (Oslo Sequence 8) Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The Great Gold Robbery Bubble in the Bathtub

Bubble in the Bathtub Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: Time-Travel Bath Bomb The Bat

The Bat Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe.

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder: The End of the World. Maybe. Silent (but Deadly) Night

Silent (but Deadly) Night Who Cut the Cheese?

Who Cut the Cheese? Headhunters

Headhunters The Jealousy Man and Other Stories

The Jealousy Man and Other Stories Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle

Harry Hole Mysteries 3-Book Bundle The Thirst

The Thirst The Son

The Son The Redeemer

The Redeemer The Kingdom

The Kingdom The Snowman

The Snowman The Redbreast

The Redbreast Phantom

Phantom Macbeth

Macbeth The Leopard

The Leopard Blood on Snow

Blood on Snow Midnight Sun

Midnight Sun The Redbreast (Harry Hole)

The Redbreast (Harry Hole) The Devil's Star

The Devil's Star Cockroaches

Cockroaches The Magical Fruit

The Magical Fruit The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel

The Snowman: A Harry Hole Novel Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder

Doctor Proctor's Fart Powder The Cockroaches

The Cockroaches Knife

Knife Phantom hh-9

Phantom hh-9 The Redbreast hh-3

The Redbreast hh-3 The Redeemer hh-6

The Redeemer hh-6 The Leopard hh-8

The Leopard hh-8 The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel

The Leopard: An Inspector Harry Hole Novel The Great Gold Robbery

The Great Gold Robbery Police hh-10

Police hh-10 The End of the World. Maybe

The End of the World. Maybe The Thirst: Harry Hole 11

The Thirst: Harry Hole 11 Nemesis - Harry Hole 02

Nemesis - Harry Hole 02 The Devil's star hh-5

The Devil's star hh-5 Time-Travel Bath Bomb

Time-Travel Bath Bomb